Crisis of confidence

Few things are worse for an economy than a banking crisis. The forceful regulatory response to recent US bank failures was warranted to reestablish confidence in our financial institutions.

What happened

Bank runs are usually preceded and often caused by a deterioration in asset quality. In the case of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), there were large unrealized losses in its securities portfolio.1 Attention to those accrued losses, coupled with revelations that startup and tech-centric businesses forming the core of the bank's customers were drawing down deposits to fund their operations, ignited fears of insolvency risk. A very high proportion of the bank's deposits were uninsured, meaning that a concentrated customer base had a lot to lose if SVB failed.2 Amid concerns that such a reality might transpire, depositors exhibited herd behavior with hastily initiated withdrawals to protect one's own interests at the detriment of the whole. Depositors called for their money back in waves that breached the bank's available liquidity, prompting regulators to shut down SVB after it closed for business on March 9 with a negative cash balance of $958 million, as a staggering $42 billion in withdrawal requests were made that day.

A bank run is some combination of rational economic-maximization of one's own self-interest and social contagion. For an institution that is insolvent but yet to be closed by regulators, a bank run is completely rational given the first-mover advantage amid impending failure. For an institution where the assets are good but illiquid, and customers all want their money back now for spurious rumor-based reasons, such a bank run is purely social contagion. Because one never has perfect transparency into how healthy a bank actually is (that includes regulators), a bank run always seems to be a confluence of the two. Deteriorating asset quality alone often isn't enough to upend a bank, but when customers speculate on the severity of the losses on the bad loans (or losses on good Treasury or MBS securities) the resulting social contagion causes deposit flight, and the more deposits lost, the more tenuous the bank's situation as liquidity evaporates and a fire sale of assets is required to meet withdrawals, meaning more reason for the next customer to want their money back.

SVB is unique in its gross mismanagement of interest rate risk, while the proximate cause of collapse is anything but. Virtually any bank would fail due to illiquidity (i.e., having insufficient cash to pay back depositors) given a sufficiently large run on its deposits. A crisis of confidence tends to be self-fulfilling, and is often why the most fervent attempts to reassure depositors or investors fail. By the time you feel the need to say that you are good for the money it is often too late. The timeless Walter Bagehot said, “Every banker knows that if he has to prove that he is worthy of credit, however good may be his arguments, in fact his credit is gone.” This was certainly the case for Credit Suisse, as the once proud Swiss national champion was forced into a shotgun marriage with rival UBS less than two weeks after SVB's collapse. Incongruous with SVB, Credit Suisse didn't appear to suffer a severe deterioration in asset quality, but the bank's recent history of sleepwalking from mishap to scandal and back created a sordid aura of bad vibes that bank officials and regulators couldn't repair. A feedback loop of negative press, falling share price, and deposit flight reached a crescendo when Credit Suisse's largest shareholder (the chair of the Saudi National Bank) maladroitly exclaimed on Bloomberg TV that it would "absolutely not" invest more capital in the reeling bank.3 Those two words proved too much to recover from as a liquidity guarantee from the Swiss National Bank was not enough to stabilize Credit Suisse. A forced takeover by UBS occurred days later and those two words will be ignominiously remembered. A crisis of confidence is difficult to overcome.

The danger of banking crises

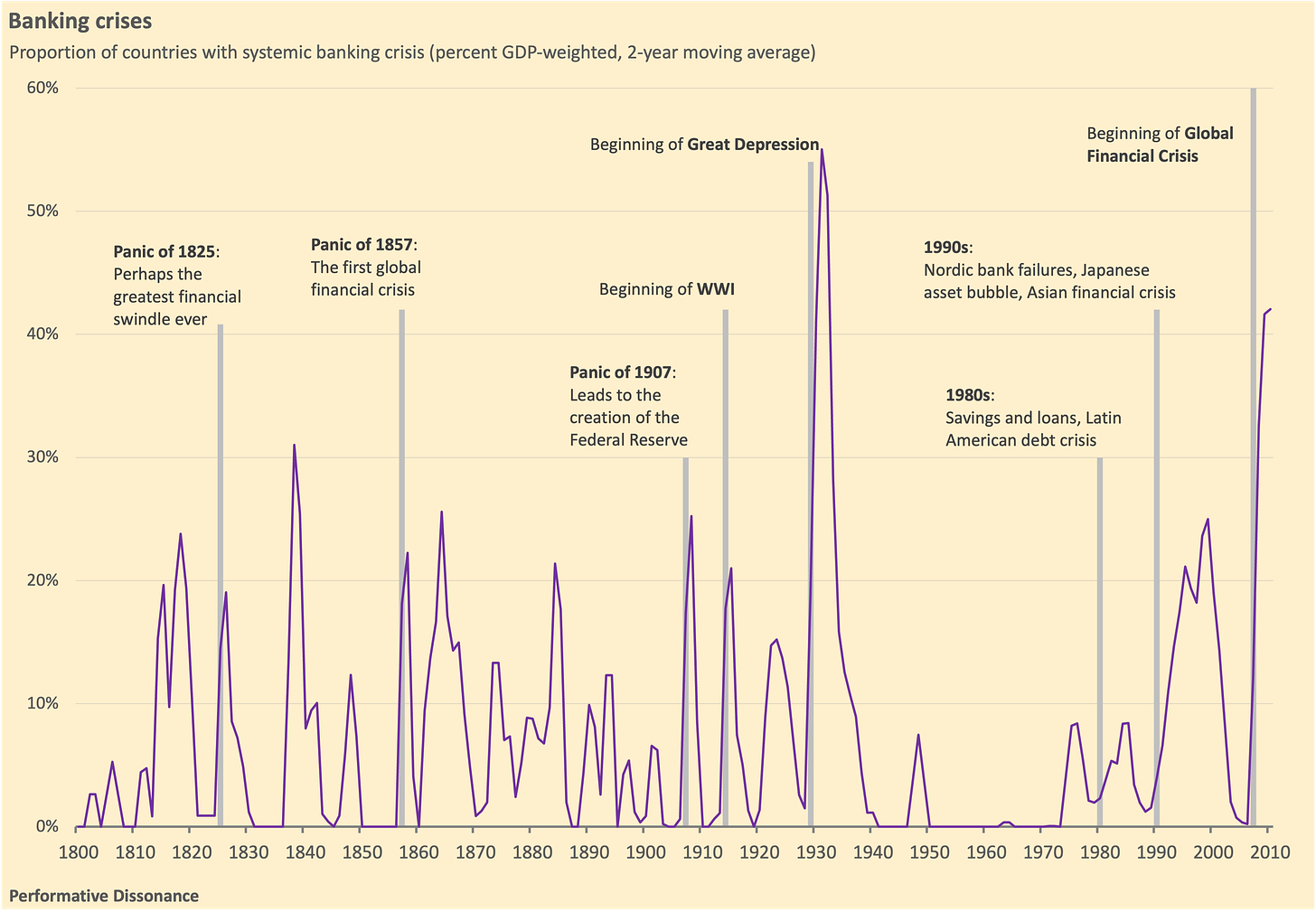

Banking crises remain a risk to countries big and small, rich and poor, democratic and autocratic, highly regulated and laissez-faire. We have yet to see any country outgrow banking crises and last month was a stark reminder. The long view contextualizes our current situation as more typical than it feels. Despite our best regulatory efforts, we are unlikely to ever live in a world absent banking crises:

Banking crises are dangerous because they make for especially deep and protracted recessions given banks are so integral to the functioning of an economy. An economy is an amorphous web of allocation decisions among scarce resources. One of the key resources is savings; a well-functioning economy matches excess money (savings) to the borrowers with productive uses for it. Such a process means the best projects get funded and in aggregate we all benefit. This matching of lenders and borrowers occurs at various levels of the economy, with the largest being the capital markets. Banks, however, are arguably the most important player as they pool society's savings and do the due diligence to determine how to lend and monitor the funds. Banks are the stewards of society's assets.

There are positive externalities associated with depositing your money in the bank, because cash under your mattress cannot be lent to anyone. If everyone in your hometown buries their life savings in $100 notes in the backyard, there is no money to lend to local businesses, or homebuyers, and interest rates are much higher as a result, stifling economic activity. A society trusting and using its banking system creates a network effect of lending allocation, reducing interest rates and providing funding and diversification for risky projects. Given the benefits associated with households and businesses trusting banks and the importance of prudent lending, the banking industry is highly regulated to give customers faith that their deposits will be available when needed. Requirements that banks obtain charters, pay deposit insurance to the FDIC (insuring up to $250,000 during normal times), and maintain specified leverage and liquidity ratios all serve to provide public trust and encourage participation in the system.

When confidence evaporates, fewer loans are made at more onerous terms since banks become more risk-averse, and the economy slows as a result. A slowing economy means businesses make less money and struggle to pay down their loans, causing banks to write down the value of these loans, reducing their capital buffers, and engendering greater risk aversion, and so on. The impact is procyclical and tends to make for deep and protracted recessions. During the Great Depression nearly half of US banks failed, severely diminishing the country's capacity to provide and effectively allocate credit. Rebuilding the economy's lending ecosystem took time, and Ben Bernanke (later Federal Reserve chairman in 2006 and a key helmsman during the Global Financial Crisis) argued that the impairment of the financial system was a chief reason that the Depression persisted—start-again-stop-again for a decade rather than the typical recession duration of one to two years. Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff provide an exhaustive analysis of the impacts of banking crises across the globe from 1800 to 2008 in This Time Is Different and their findings are sobering:4

Asset markets are hit especially hard. Real housing prices fall an average of 35% over six years and equity prices tumble an average of 56% over about three-and-a-half years.

The associated recessions are brutal. Unemployment rates rise by an average of 7% and real output-per-worker decreases more than 9% on average.

Government debt drastically rises. On average, three years after the crisis government debt increases 86% in real terms relative to the precrisis level.

Their results span two centuries and cover 66 countries, but don't take into account the GFC given their dataset ends in 2008. It might be convenient to dismiss those findings as the product of bygone eras or inflated by extreme shocks in developing countries with institutions less robust than our own. But now consider the case of the US during the GFC: homes prices fell 27%, the stock market decreased 57%, unemployment rose from 4.4% to 10.0%, real output-per-worker fell 5.1%, and government debt increased 72%.5 We've yet to see a country outgrow banking crises and the GFC experience reminded how problematic they are. The point of providing this context is not to fear monger, but to underscore the importance of swift regulatory action to restore confidence in the system. Response should error on the side of preventing a financial crisis.

"Bailing out" troubled banks in the form of a forced sale at a favorable price (the case with Credit Suisse), providing emergency loans equal to par value rather than market value of collateral (the Federal Reserve's new Bank Term Funding Program), or taking the most toxic assets of a troubled institution onto public balance sheets (also Credit Suisse, and Signature Bank—another failed US bank in March) all come with a cost to the public. But the preponderance of public costs stemming from banking crises are those associated with a recession or depression, should they ensue. Government indebtedness didn't increase 86% on average during bank crises because of the cost of bailouts (there are explicit and implicit bailout costs costs, and they are notoriously hard to measure6), but as a result of plummeting tax revenues on the back of severe output contractions. In these cases an ounce of bailout is worth a pound of fiscal stimulus.

Regulatory error

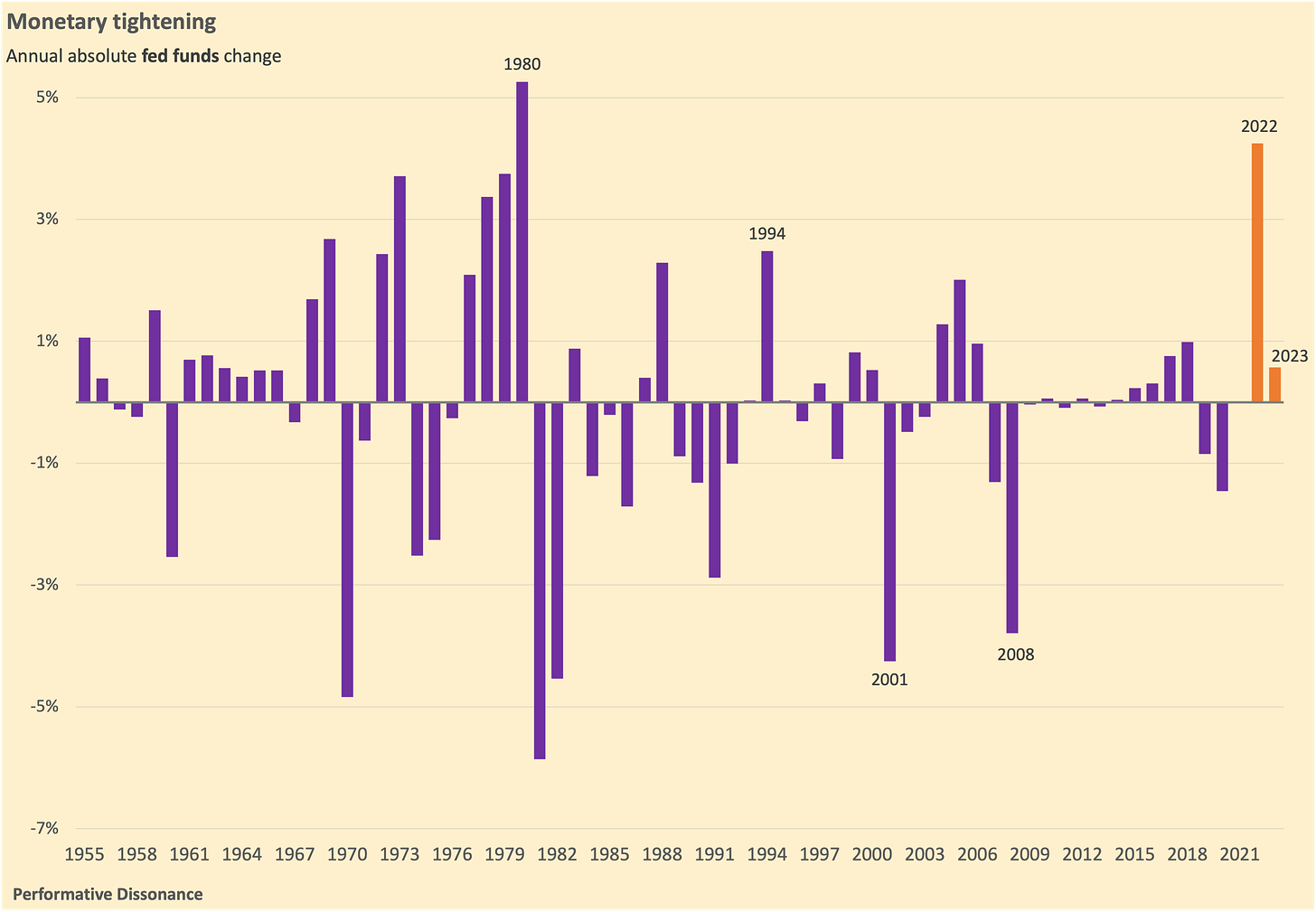

Regulators and policymakers undoubtedly deserve blame for our current predicament. The most egregious instance was increasing the size of banks covered by the core Dodd-Frank act provisions from $50 to $250 billion back in 2018.7 Banks with assets below $250 billion were no longer subject to stress tests and liquidity metrics like the liquidity coverage ratio and net stable funding ratio.8 SVB and Signature Bank,9 the two US banks to fail in March, were both gifted a reduced regulatory burden by the 2018 legislation. While it is impossible to say that the banks wouldn't have failed were they still subject to the meat of Dodd-Frank, being removed from the Fed's annual stress testing might have made their vulnerabilities more visible to regulators, or so the thinking goes. While the massive interest rate risk of SVB was hiding in plain sight on the bank's financial reports,10 there is actually reason to think that the annual bank stress testing wouldn't have caught it. Stress tests are forward-looking exercises that evaluate the impacts on financial institutions given severe but possible circumstances. Federal Reserve (Fed) stress tests feature baseline and severely adverse scenarios. Every worst-case circumstance since 2015 featured interest rates falling to nearly zero. The severely adverse scenario of the 2023 stress test, whose results will be available in June, also involved rates decreasing to "near zero." Such a reduction is realistic based on historical scenario analysis since interest rates usually fall during economic downturns, but misses the mark when it comes to identifying risk sensitivity in the country's banks at present. The 2023 scenario choice seems especially peculiar given how obvious the risks of rising interest rates are, as the Fed hiked the benchmark fed funds rate more during 2022 than any calendar year since 1980:

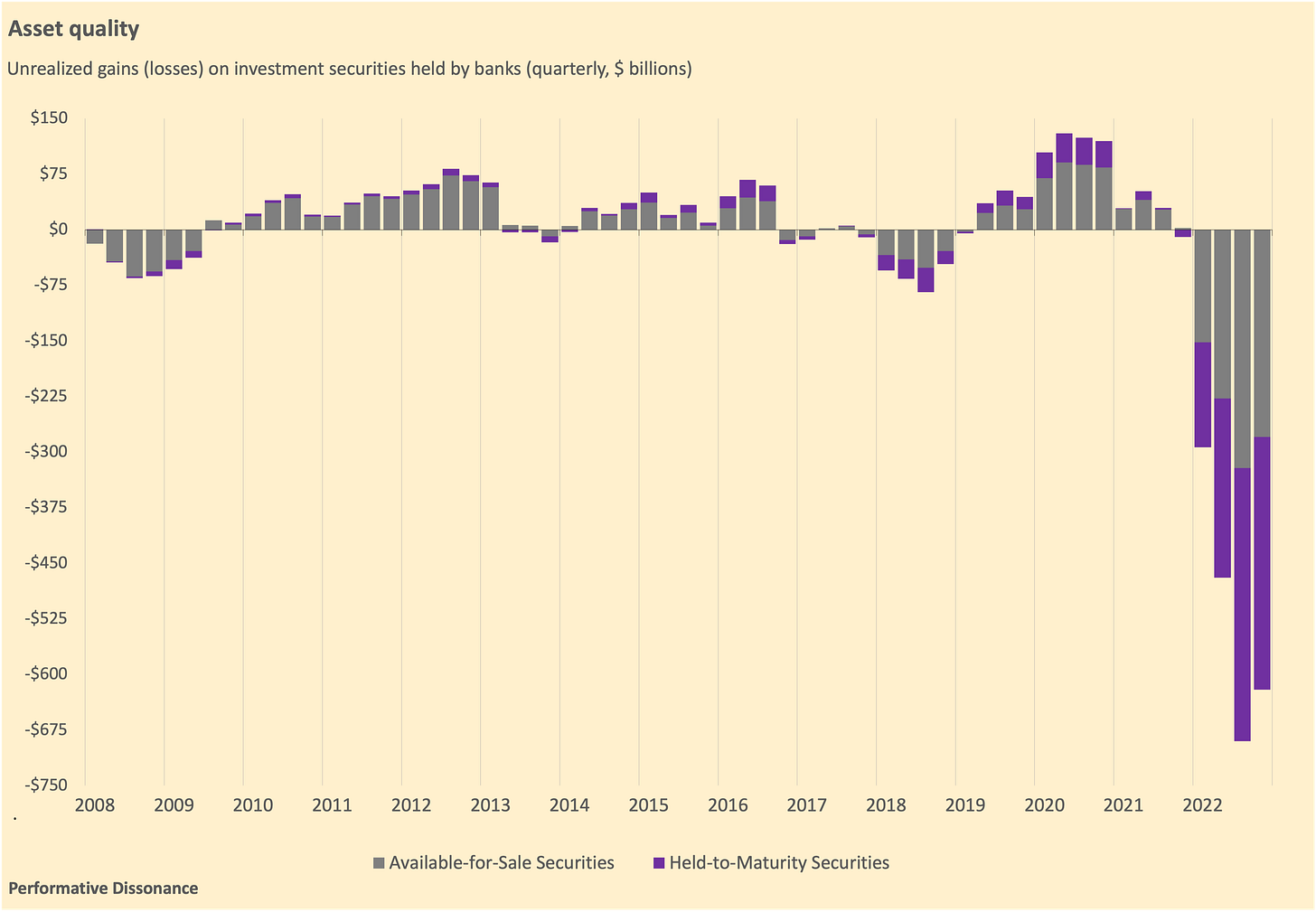

Further, regulators were well-aware in late-2022 that rising interest rates led to large unrealized losses across the banking system. When a bank like SVB buys a fixed income security there are two potential accounting designations: available-for-sale (AFS) or held-to-maturity (HTM). The AFS designation involves holding the assets at market value, where a drop in price means reduced book value of assets and equity. For a bank, leverage (the ratio of assets to equity) is highly regulated to ensure there is a sufficient capital buffer of equity to protect depositors and other creditors from insolvency. Better to close a bank with a deteriorating slice of equity than to wait until the equity is incinerated, in order to ensure depositors are covered. An asset designated AFS that suffers unrealized losses will reduce a bank's assets and its equity, thus increasing leverage and reducing the available assets to pay back deposits.

The other accounting option, HTM, reports securities at "amortized cost," essentially nerd-speak for holding the asset at the price you paid for it, with relatively small (compared to changes in market value) adjustments made each quarter to amortize the premium or discount paid over the life of investment. HTM designation means there is no intent or expected need to sell and the securities' value on the balance sheet is insulated from price changes. If a security marked HTM loses value those unrealized losses aren't reflected by decreasing assets or equity, even though the economic reality is the same as if it were AFS: there are fewer available assets to pay back deposits.

Rate rises illustrated in the previous chart mean losses on fixed income investment securities across banks, as seen below. These losses were known to regulators as they collect, monitor, and collate the underlying data, referenced explicitly in February 2023 speech from FDIC chairman Martin Gruenberg who noted $620 billion in unrealized losses across the banking sector as of 2022Q4.

HTM losses were the sword of Damocles hanging over SVB. As of 2022 year-end the bank had $15.1 billion in unrealized HTM losses on a $91.3 billion HTM security portfolio with a $16.3 billion equity cushion. Accounting designations mandate that should one HTM security be sold prior to maturity, then all like securities given that designation must be reclassified as AFS. This means the unrealized losses would then reduce the bank's book value of assets and equity, making it nearly insolvent and requiring an equity raise. Depositor withdrawals increased the probability that SVB would need to tap into its HTM securities for liquidity, and the consequences of doing so prompted the ensuing bank run that proved overwhelming.

That SVB's management didn't have material insurance against rising interest rates going into 2022 is perplexing and an utter failure in risk management. That regulators weren't tapping SVB on the shoulder by the end of 2022 to raise equity is surprising yet also somewhat unsurprising. Solvency risks posed by the unrealized losses marked a clear potential path for deposits to be put in jeopardy, and thus an argument for intervention. Had regulators ordered the bank to raise capital to increase its equity buffer for loss absorption (as SVB tried to do on March 8), equity owners and customers might have interpreted the move as a mark of serious weakness, prompting a run and precipitating the very activity that could bring down the bank. So it's possible regulators were aware of the risk but consciously decided that doing nothing was the best option. If depositors did nothing and interest rates eventually fell such that the asset values recovered then the unrealized losses would go away and you'd be reading about something else right now. It's also possible that regulators missed this risk. A third and most likely possibility is regulators deemed the probability of deposit outflows large enough to force selling of the HTM portfolio so low that they didn't even register the outcome as a risk.11 Whatever the answer, there were regulatory deficiencies leading up to the failure.

Regulatory success

We should be able to distinguish between regulatory deficiencies prior to the bank failures and regulatory success in preventing a propagation of banking crisis. Firefighting is a useful analogy here on a few levels. First, there are two separate and important means of reducing risk of fire: prevention and emergent intervention. On the prevention side, we have laws against starting fires and there are a litany of building codes mandating the use of retardant materials. On the intervention side, there are laws appropriating resources to immediate response in the event that fire occurs. These two approaches work in tandem, where the failing of one doesn't indicate the failing of the other. Importantly, when a fire does occur the firefighters arriving on the scene are tasked with extinguishing the blaze in a manner that minimizes the spread to adjacent infrastructure. The job of the first responder isn't to determine whether negligence was a factor in igniting the flames, the goal is to ensure they don't become a conflagration. No fire chief willingly allows a house to burn down because the inhabitants didn't abide by building codes or overlooked snuffing out their candles. A bank failure is no different.

Regulators were criticized for guaranteeing deposits at SVB and Signature above the FDIC threshold of $250k, as detractors cried cronyism. This mindset is parochial and understates the importance of the moment. Had SVB and Signature deposits not been guaranteed by regulators, it would be analogous to allowing a building to burn in order to send a message to owners and inhabitants: Look what happens when you don't take fires seriously. This isn't how the system should work and it would risk setting the entire town ablaze. Our capitalist society is built on specialization and trust. When I move into a new apartment building I am doing so under the assumption that the building is in compliance with local codes, the fire extinguishers work, sprinklers are functioning, and the fire department will promptly respond to an incident. Being a tenant shouldn't require being well-versed in local building codes and an adept inspector. We have specialists for that sort of thing such that tenants can specialize in something else. Similarly, we cannot expect households and businesses depositing money into a bank to also be capable bank examiners. The moral hazard argument used against the guaranteed deposits is in effect arguing that anyone who uses a bank must be qualified to assess the safety and soundness of that institution. That is the job of specialists! And they are paid handsomely to do it. The banking specialists who failed were SVB and Signature managers, equity analysts and investors, and the regulators and examiners meant to safeguard against such an outcome. The companies and individuals who happened to use those banks shouldn't be punished as a result. Some might admonish bank customers with accounts far in excess of the FDIC limit, but this argument breaks down when considering large clients (especially corporate ones) of the likes SVB catered to have to keep their cash somewhere (43% of US deposits were uninsured as of the end of 2022).12 We have a sophisticated apparatus of bank regulation that should ensure the public doesn't need to moonlight as bank examiners. Allowing failures of SVB and Signature to put depositor funds in jeopardy would seriously undermine trust in the US banking system and would risk social contagion.

To be clear, when it comes to bank failures, depositors should be protected while equity owners are wiped out and non-deposit creditors bear the residual losses. This is exactly how the bank failures have played out thus far in the US (the Credit Suisse forced sale was an absolute mess and is likely to damage the reputation of the Swiss banking system). I am much more sympathetic to a moral hazard argument from the standpoint of bank managers and owners, rather than of depositors. If a bank bailout protects equity holders and senior managers, then that unequivocally promotes excessive risk taking from the bank. From the equity owner's perspective such a circumstance is heads I win, and tails the public loses, since they are bailing me out. This is not the sort of bank "bailout" we've seen so far in 2023, but is more analogous to those of the GFC when the US government recapitalized the nation's largest banks through the Troubled Asset Relief Program.13

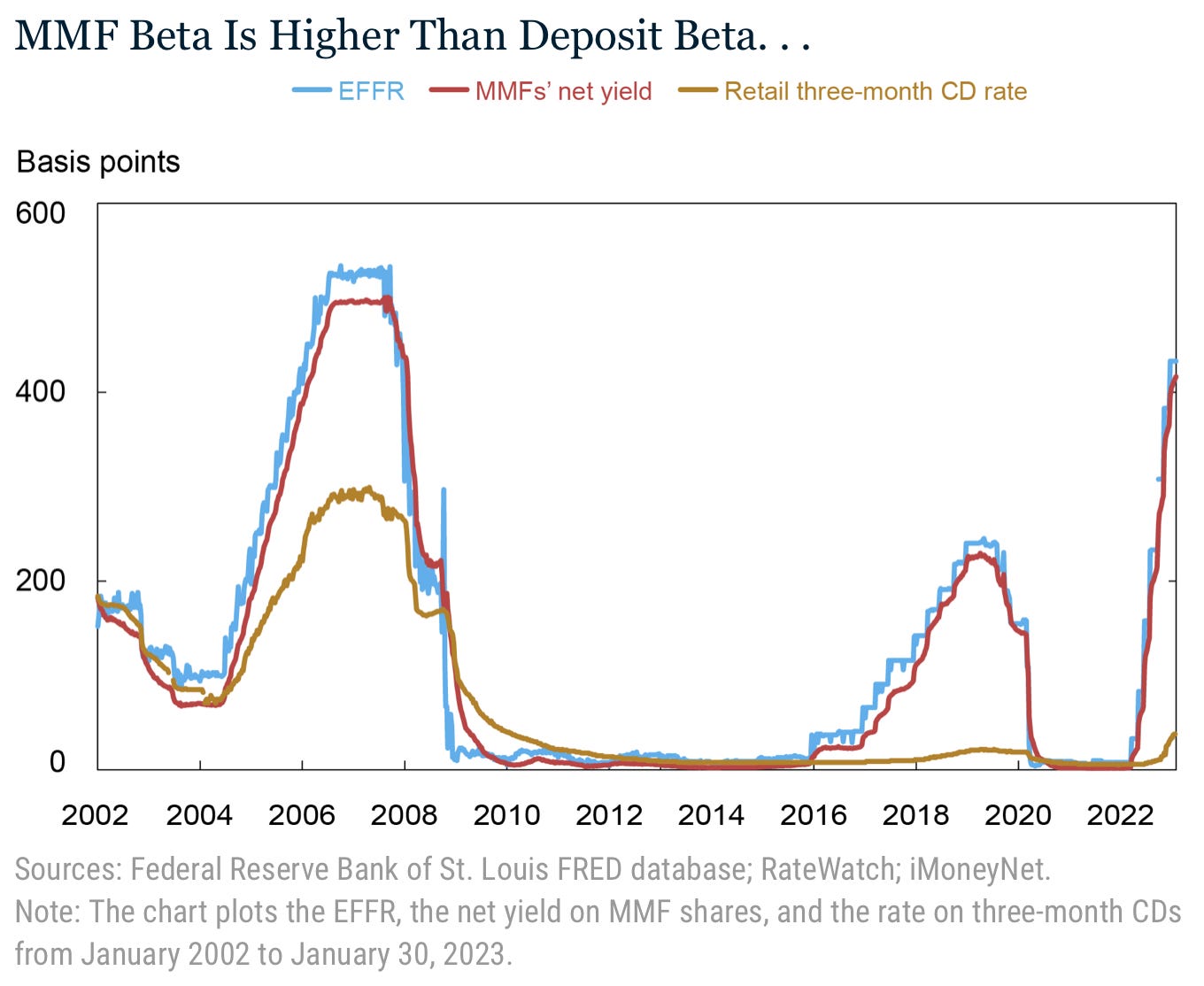

The swift action of the regulatory response is more critical when we consider the current state of the overall US banking sector. Banks in aggregate have been losing deposits since the beginning of the post-Covid Fed tightening cycle in March 2022, with the deposit peak coming in mid-April of last year. When rates are rising, banks are usually slow to pass them on to their customers in the form of higher interest on deposits. This is positive for bank profitability if they are able to increase the rates they charge on their loans faster than they increase the rates they pay depositors, resulting in a higher net interest margin (NIM), a key marker of bank profitability. If banks hold mostly fixed rate securities, like Treasuries and MBS, then upping the rate paid on deposits will decrease NIM, so the bank is unable to pay higher rates without suffering economically. With the fed funds rate bouncing within the 0 to 0.25% target band for most of post-GFC period, bank customers were resigned to earning nothing on their deposits because earning something would require assuming credit risk or interest rate risk. But when the fed funds rate moves above 0% an investor can earn essentially that rate with nearly zero risk by investing in money market funds (MMFs) that hold Treasury bills or other short-term assets (BIL is the largest MMF ETF and its assets doubled to $3 trillion since January 2022). Deposit beta is the portion of a change in the fed funds rate that flows through to the rates paid to bank depositors. A recent report from the FRB of NY found that banks passed on only 8% of the increase in the fed funds rate (as measured by three-month retail CDs) since March 2022 while MMFs passed on 97% of the increase. The following chart illustrates just how uncompetitive the rates paid by banks are (yellow) relative to MMFs (red).

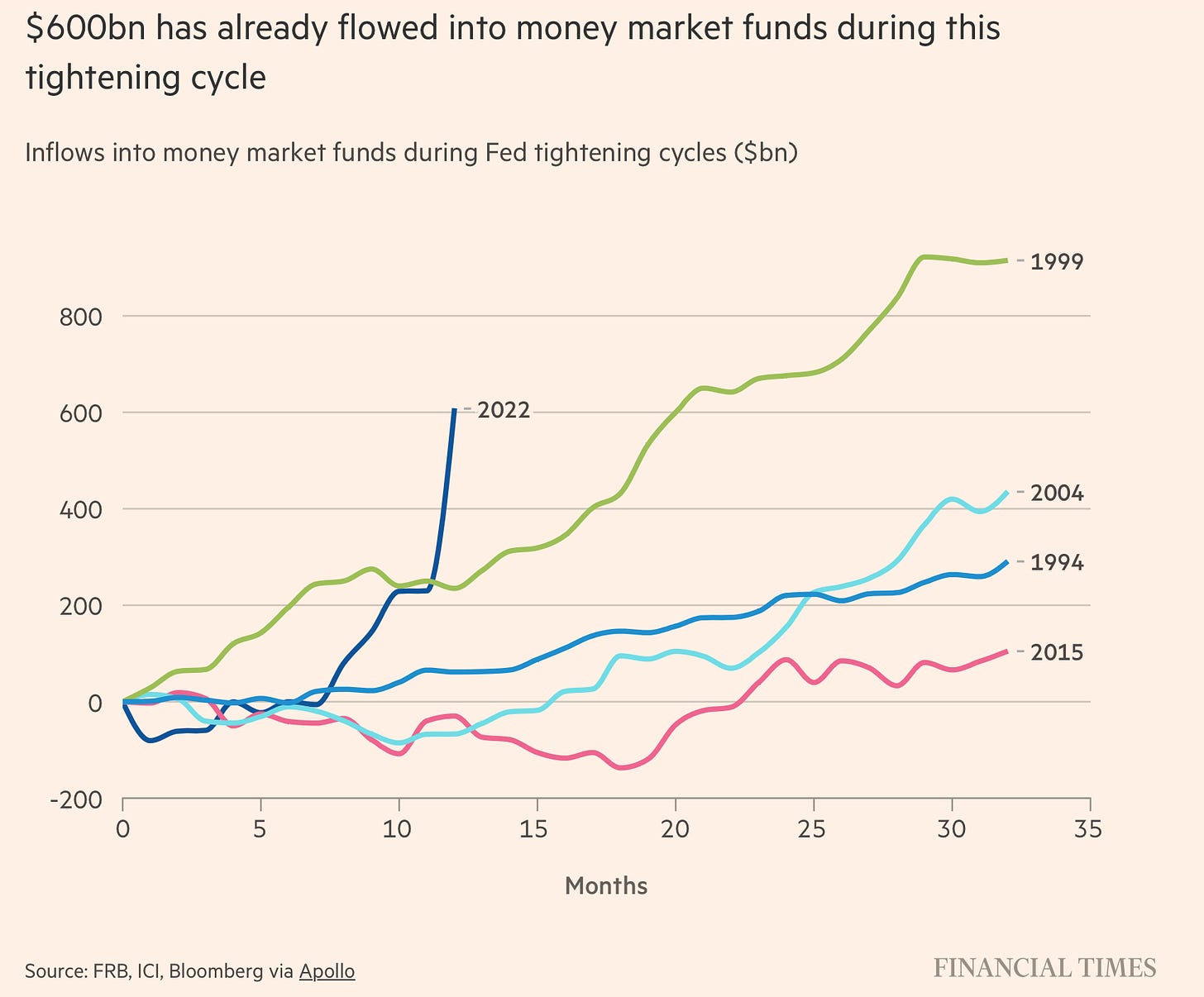

With this in mind, the over $900 billion reduction in bank deposits we've seen since March 2022 should be unsurprising. Holding unused cash at a bank comes at the cost of interest that could be earned investing in MMFs, roughly 4.6% at the time of this writing. Deposit withdrawals are standard during tightening cycles due to low deposit betas, but the current experience is extreme. The nearly $1 trillion reduction in bank deposits from peak is the most on record dating back to 1973, and roughly a half-trillion in deposits walked during March. The flow into MMFs is much faster than during the four previous tightening cycles:

What it means

Money market inflows are currently occurring at the fasted rate since April 2020 (after we sold everything and scrambled for safety). Some of this is due to the difference in deposit betas, but the recent uptick is likely spurred by concerns over the health of our banks. It seems we collectively started paying attention to how we bank during March and furiously shifted deposits out of and within the banking system. Banks offering higher yields or perceived to be less risky benefitted, while MMFs and mattresses also received a cash influx. This deposit drain and reshuffling is likely to pose additional risks to banks as they either sell assets to cover the outflows or source liquidity and up their leverage. This uncertainty means banks will be more conservative with their balance sheets, increasing underwriting standards and issuing fewer loans. The result will be a drag on economic activity.

SVB and Signature were especially precarious in their high proportion of uninsured depositors (94% and 89%), making a run more likely. Across the entire banking system 43% of deposits were insured as of the end of 2022. But SVB and Signature weren't alone in accumulated losses on their balance sheets. Earlier we cited the $620 billion in unrealized losses across banks on their investment securities. But such investments comprise only a portion of assets, with the other important component being the actual loans that a bank makes. Often bank loans are floating rather than fixed, meaning that the interest rate charged changes with a benchmark rate (e.g., credit cards). So these loans haven't suffered the same losses as investment securities (nearly always fixed rate) due to rising interest rates, but they are susceptible to the credit risk of the borrower, who is likely to have more trouble meeting the loan obligations as rates rise (I covered this dynamic in Acute mountain sickness and interest rates). Fixed rate loans (e.g., mortgages) are losing value as interest rates rise and floating rate loans (e.g., credit cards) are losing value as economic conditions suffer.

Estimates of losses across the banking system vary, but they are large. One recent paper estimates banks have $2 trillion in unrealized losses across their assets, while another reckons that amount is $1.7 trillion. These numbers are concerning given that total bank equity as of the end of March was $2.1 trillion. That is, should these losses be realized or redesignated AFS, by say a massive bank run, they would be nearly sufficient to make US banks insolvent in aggregate. There is a relatively thin slice of equity protecting bank deposits, and it's within this context that we should judge the recent regulatory intervention.

Continued interest rate increases from the Fed will result in more losses on bank security portfolios and will incentivize more deposits moving from banks to MMFs. Procyclicality is everywhere! Once again, inflation is the variable worth watching as the longer it remains elevated, the tougher the Fed's decision between prioritizing financial versus price stability. This current paradigm shouldn't be considered an extension of the GFC period where financial institutions mispriced risk and failed en masse or were bailed out. This is something entirely different. We are undergoing a generational shift from economic loosening to tightening, and so far the duration and magnitude of tightening has been completely underappreciated (that includes me!). Banks built up massive balance sheets during the prior economic regime of low and lowering rates and are now facing the consequences of bringing that balance sheet into a different environment. In extreme cases like SVB, banks are so constrained by their balance sheets that they cannot afford to pay meaningful interest on their deposits.14

Confidence in our financial institutions is the difference between an orderly financial tightening and finding out exactly how bad some of these balance sheets are. As long as rates are high or rising there remain risks that something breaks. There is cause for optimism in that accumulated losses can be reversed by a transition to cutting rates from raising them, but that requires first taming inflation. Regulators deserve credit thus far for their response post-failure to stem a crisis of confidence and the introduction of emergency measures to prevent a mass run on deposits, or a mass flight from small banks to large ones.15 The Fed's emergency BTFP facility will help banks meet their funding needs, and the guarantee provided to depositors of failed banks likely prevented further runs. Crisis averted is benefit unseen.

As of the end of 2022 SVB had $15.1 billion in unrealized losses in its $91.3 billion HTM securities portfolio, the largest portion of its $212 billion total assets. These losses were nearly as large as the bank's $16.3 billion equity position.

93.8% of SVB's deposits were uninsured, the most among US banks with over $50 billion in assets. FDIC insurance guarantees deposits up to $250k.

These two words are not the entire story. The full quote from Ammar Al Khudairy was, "The answer is absolutely not, for many reasons outside the simplest reason which is regulatory and statutory," in reference to additional regulatory requirements if the SNB upped its holding beyond 10%. While the underlying message was sensible, the delivery was unnecessarily curt and couldn't have come at a worse time.

Reinhart, Carmen M.,Rogoff, Kenneth S.. This Time Is Different. Pages 224-225. Princeton University Press

Housing prices are nominal and measured by the S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index , the stock market measured by the S&P 500, unemployment rate measured as U-3 , real output measured as real gross domestic product per capita , and government debt is nominal measured as increase in total public federal debt three years after the recession (2012Q2) relative to 2007Q4.

This Time Is Different . Table 10.9. Pages 163-164

The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was the landmark legislation meant to bolster the transparency, supervision, and resilience of our financial system in the wake of the GFC, along with Basel III.

These ratios are essentially two separate ways of measuring a bank's ability to deal with deposit outflows. The LCR considers available emergency liquidity via a ratio of high quality assets to outflows over a 30 day period with deposit flight and reduced access to funding, while the NSFR considers structural liquidity of a bank's balance sheet.

Signature Bank's risks were concentrated customers, a high proportion of lending to technology and cryptocurrency companies, and a striking 89% of deposits were uninsured. Like SVB, this was the perfect setup for a bank run: suspect asset quality and depositors with an incentive to flee if the going gets tough. The SVB event further subverted the faith of Signature's depositors as withdrawals reached 60% of 2022 year-end deposits. Ironically, Barney Frank, whose name is borne on the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act—the landmark legislation meant to bolster our financial system in the wake of the GFC—as a cosponsor, was a board member of Signature Bank when it was closed by regulators on March 12.

There is speculation as to the trigger for the crisis of confidence in SVB and the subsequent run. SVB released 2022Q4 results on January 19 and a month later Byrne Hobart at The Diff identified the large unrealized losses. Hobart has a large following in the venture capital community and his newsletter exposing the fragilities is thought to have prompted concerns about the safety of deposits.

SVB had a buffer of cash and AFS securities of $39 billion that could be used to cover outflows prior to a forced selling of the HTM portfolio, plus potential options for off-balance sheet borrowing. Realistically it would take less than the $39 billion to trigger a severe liquidity crisis at the bank, but the point is that there was ample liquidity for the normal course of business.

Being a large depositor comes with tradeoffs. You can prioritize income, safety, or banking services, and all have limitations (companies banking with SVB seemed to be optimizing for banking services). If you were obsessed with safety you could hire a corporate treasury to make and operate accounts on your behalf with other banks to ensure the totality of your assets are FDIC insured. There will be operational limits on the number of accounts that can be connected to your custodian bank and not all banks can accept brokered deposits, but let's ignore that. There were about 4,700 FDIC insured banks at the end of 2022 and a corporate treasury company could theoretically spread $250k across each bank and thus allocate $1.175 billion safely across the US banking system. Even this theoretical breaks down at scale. First, companies routinely send and receive amounts in excess of $250k, so all assets cannot be covered all the time. Second, $1.175 billion isn't that much money for a company. Roku was one of SVB's largest clients and had $487 million of its total cash and cash equivalents of $1.9 billion parked at the bank. So even if Roku found a treasury service provider that could open an account with every bank in the US there just aren't enough banks for its cash to be covered by FDIC insurance. And by doing this, Roku would be accepting a lower level of banking service than it received from SVB, because banks trade services for deposits. One would assume most of Roku's cash was parked in money market funds—we'll discuss them shortly—but assets at a broker aren't federally guaranteed either. And Roku isn't even a particularly large company.

Deeply unpopular but also warranted and necessary given the catastrophic consequences of large-scale bank failures beyond those experienced.

Banks received record deposits during the post-pandemic period (SVB deposits grew 85% during 2021 alone) and needed to do something with those inflows. The US government was borrowing record amounts via Treasury issuance and mortgage origination also topped the previous high of 2003. Treasuries and MBS were convenient securities for banks to purchase given their abundance and ability to provide an interest rate spread on deposits. Additionally, as part of Basel III banks are assigned minimum capital requirements relative to their risk-weighted assets, meaning more risky assets require more capital. HTM Treasuries hold a 0% risk weight (the same as cash) and HTM MBS issued or guaranteed by the US government holds a 0 to 20% risk weight, meaning balance sheets could be expanded by buying these securities with little to no need to increase capital (i.e., issue equity). By buying these securities banks could increase their economic leverage without increasing their regulatory leverage. These assets were great investments when rates were low and falling but poor investments when high and rising. Generally speaking, the more Treasuries and MBS that a bank purchased during 2020 and 2021 at historically low rates, the larger its current unrealized losses on those securities, assuming it didn't hedge the interest rate risk. Banks bought nearly $2.3 trillion in securities from the beginning of 2020 to the end of 2021. They've effectively locked in historically low rates received on assets and paying rates in excess of them on deposits would result in a negative NIM.