Acute mountain sickness and interest rates

When traveling to a high-altitude environment, the absolute elevation and the rate of ascent both matter. The same is true for the effects of rising interest rates on economies

Level, abruptness, and time matter for elevation and interest rates

If you fly to Denver from a coastal city and immediately drive to one of the state's mountain towns you might be bothered by the high elevation, with symptoms such as headache, dizziness, or nausea. You're almost guaranteed to experience these disturbances if you wake up in Wichita, Kansas (1,300 feet) and drive to the top of Colorado's Pikes Peak (14,100) by sunset. For an unacclimatized person that adventure would cause acute mountain sickness (AMS), the medical term for a deficiency of oxygen reaching a person's tissues (hypoxia)—fatal in the worst cases as AMS progresses into high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) or high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE).

Altitude's effects are instructive because elevation matters both in the absolute and relative sense. In absolute terms, you just won't function quite as well at 10,000 feet as you will at sea level, no matter who you are (the level matters). But someone who lives at 10,000 feet will function much better on top of Pikes Peak than someone who woke up in Wichita (the abruptness matters). This is the obvious concept of acclimatization, where our bodies adjust well to hypoxia but the process takes time.

There is also a time element. Outside of medical intervention, the best way to improve AMS is to descend. Remaining at high elevation after a rapid ascent can cause symptoms to worsen, although it could also result in acclimatization. At a sufficiently high altitude, the more time spent there, the greater the danger. The "death zone"—generally considered about 26,000 feet—is where oxygen pressure is so low that rudimentary processes of sleep, digestion, and even thought become herculean tasks absent supplemental oxygen. Your physiology begins shutting down and the only option is to descend.1

As altitude profoundly impacts physiology, interest rates profoundly impact economic systems. Warren Buffet famously quipped, "interest rates are to asset prices what gravity is to the apple." The impacts extend far beyond the pricing of securities to the very function of markets that enable the fluid transfer of assets between parties. Crucially, the absolute (level), the rate of change (abruptness), and the duration at an elevated level (time) all matter. For one country that has had 10% interest rates for a decade, its financial and economic systems might be healthy and growing as they're accustom to that rate. In contrast, if another country went from a 0% interest rate in the morning to a 10% interest rate in the evening, the impact would be ruinous. It would likely take a heroic policy intervention to prevent a full blown financial crisis.

In past newsletters I mentioned the danger of high and rising interest rates to the economy. Specifically, the notion that more time spent at higher rates increases the likelihood something breaks, and when dislocations occur they stress other areas of the financial system, and those stresses amplify. I used the term polycrisis (popularized by Adam Tooze) to connote the interconnectedness of risk, describing a system where the risk of the whole far exceeds the sum of the parts. In considering the possibility of a polycrisis-type scenario where you have the impairment of a causally entangled system, my intention wasn't to issue a prediction but a warning, a possible outcome rather than an expected one. This newsletter explores how interest rate-related disruptions can amplify throughout the economic system to propagate larger, more complex issues that require forceful and decisive corrective policy responses. The web of interconnectedness is more tangled, fractal, and complex than can be coherently elucidated in any financial newsletter. Much as I doubt that any single person knows how everything in a smartphone works, I don't think anyone completely groks the mechanics and connections of all funding flows across all layers of the economy. (If that person exists, Zoltan Pozsar is a good bet.) Therefore, rather than providing a complete map of the interwoven and overlapping economic web, this is a description of how disruptions might amplify across financial connections.

Solvency and liquidity

Broadly speaking, there are two channels for economic failure: insolvency and illiquidity. When you are insolvent, your liabilities exceed assets and you are no longer a going concern (the business needs to begin liquidating assets to pay creditors). When you are illiquid you don't have the cash on hand required to pay your obligations, even though you may have more assets than liabilities and be a profitable business. So if you can't pay your creditors and fail to appease them before producing the necessary cash, you enter bankruptcy. Hiking interest rates works mostly through the insolvency channel. It is an effective tool for reducing inflation because economic entities on the whole become less solvent as borrowing costs rise and profit margins decrease.2 When discussing these concepts at the individual entity level (the firm or household) I use the terms solvency and liquidity, while referring to them as "fundamental" and "technical" when describing the system level.

The first-order impact of higher interest rates is to increase financing costs. Most firms use debt to finance some portion of their operations, and if the costs of debt rise then the business becomes less profitable. There are concerns that post-GFC economies characterized by ultra-low interest rates were breeding grounds for zombie corporations, loosely defined as those that require continued cheap debt financing via banks or capital markets to survive. Back to the elevation analogy: there is probably an interest rate "death zone" equivalent at the firm level (more profitable companies and those that don't rely on external financing can withstand much higher rates), where once reached, maintaining that rate leads to increasingly smaller circles around the bankruptcy or insolvency drain. A crucial question of this economic cycle is how many zombie companies are there and how soon will they start folding? Interest rate levels, abruptness, and time all matter here.

The prevalence of zombie corporations is a point of debate3 and markets remain relatively sanguine about the prospect of risky debt defaults in 2023 and 2024 (rising but roughly in line with historical averages).4 Financing stresses for zombies and non-zombies are sensitive both to absolute and relative interest rates, and the period that rates remain high. Companies relying on adjustable rate loans (often called leveraged loans) are simultaneously more exposed to rate increases and usually have lower credit quality and higher leverage than firms able to tap more favorable financing terms (i.e., fixed rate). Those borrowing on floating rate terms feel the impact of rising rates immediately as their financing costs ratchet higher. Abrupt rate rises mean sudden cost increases, which are acute strains on profitability as firms have less time to react. Larger firms in relatively more favorable positions will often issue debt to capital markets at a fixed rate rather than use bank financing with floating rates. If you issued fixed debt during 2020 or 2021, a period of record issuance that enjoyed ultra-low borrowing costs and ample liquidity to absorb the deals, you are insulated from rising rates. But the longer rates remain high, the more likely firms will need to roll their debt over into these higher rates, which may dramatically increase costs depending on the amount to refinance. Given tougher terms, firms issued the lowest amount of debt in 2022 since 2009, less than a quarter of 2021. Firms that can draw on their balance sheets to fund operations and expansions are best-positioned. Of those reliant on debt, the less near term borrowing they require and the more fixed their rates, the better.

Debt markets

The debt of one is the asset of another. The roughly $10 trillion in outstanding publicly traded US corporate debt is owned by an array of economic actors, from banks, to institutional investors, to households. The manner in which they are owned vary widely from direct ownership to open-ended investment funds (e.g., mutual funds). 2022 was difficult for the issuers of debt (they paid more for it) and those who hold the claims (the value decreased throughout the year).

Fixed income markets (debt of some manner) sold off dramatically this year, taking the double whammy of higher interest rates and widening credit spreads. Corporations are very happy they issued debt in the latter half of 2020 and during 2021, as you really don't want to issue debt with rates and spreads where they are if you don't have to.5 So far, loans (floating rate) have fared better than high yield (fixed rate) due to their lower duration profile (the price sensitivity of a bond to an increase in interest rates), but their fundamentals are still duration-sensitive since higher rates are immediately passed through to the firms' income statements. If defaults pick up, expect to see them in loans first.

The interplay at the entity and asset class levels is that rising rates are impactful on both planes. At the entity level, they reduce solvency at the margin, which reduces the likelihood that firms can meet debt obligations at the margin. So their debt becomes slightly more risky to account for the slightly higher probability of default (credit spreads rise) and the price of their bonds fall (see above). At the fixed income asset class level, higher rates mechanistically result in lower prices due to the discounting effect.

Shadow banks and money transmission

Beyond the fundamental factors that impact the solvency of corporations and households, there are technical factors that ensure ample liquidity is efficiently allocated throughout the financial system. Underpinning this elaborate network are shadow banks: bank-like entities that provide similar functions of maturity, liquidity, and credit transformation without taking deposits. These entities are bank-like because they provide critical functions to facilitate the elasticity of money—expansion and contraction of the supply of money as it is needed in the economy. A key point of the shadow banking system is that it largely functions outside the onerous regulations faced by traditional banks while lacking a public backstop (FDIC insurance, access to the Fed's discount window, etc.). Banks create money,6 shadow banks facilitate money transmission.

Mutual funds

One type of shadow bank is the open-ended investment fund, such as a mutual fund. Continuing with corporate debt, a mutual fund exchanges its shares for cash, and uses that cash to buy corporate debt.7 This mutual fund is engaged in all of the bank-like transformations since it is taking dollars (a liability of the Federal Reserve) and converts them into the liability of a less creditworthy institution through the act of buying corporate debt. When I buy shares of the mutual fund I exchange cash for shares in a fund that holds corporate loans on my behalf. For the mutual fund, the assets are corporate debt and the liabilities are cash. This exchange takes the world's most liquid, credit-free instrument (outside of something like gold which is no-one's liability) and converts it into one with more credit risk, less liquidity, and a maturation at some point in the future. This is what we mean by liquidity, maturity, and credit transformations.

To receive an investment return beyond the cash rate you have to increase liquidity, credit, and/or maturity risk. But there are additional technical risks that occur through the process of shadow bank intermediation. One risk is that a mutual fund receives a high volume of share redemptions that require paying out more cash than the fund holds. Under normal market conditions the mutual fund sells some assets to cover the redemption and the market absorbs the volume without large impacts to price (this is what we mean by a liquid market). But meeting an unusually large amount of redemptions requires a high volume of selling, and if that volume exceeds the market's depth the price of the asset being sold will fall. The selling costs of liquidating assets to pay out redemptions are born by those who remain in the mutual fund (they suffer dilution) and more selling pressure from those who leave means more dilution for those who stay. During times of market stress, where cash is preferred over more risky bonds, there is a first mover advantage to exchange your mutual fund shares for dollars quickly. In this way, much like there can be a run on a bank, there can be a run on a mutual fund. If I perceive that other investors will be running for the exits it benefits me to get there ahead of them. Investor psychology can snowball in this way. Those investors who remain in the fund during the heavy redemption periods suffer dilution as the value of the assets they hold fall to accommodate the liquidity needs of the redeeming investors. When former BOE Governor Mark Carney said in 2019 that corporate bond funds "are built on a lie," this is the dynamic he was describing. Like a bank, a mutual fund is in the business of borrowing short and "lending" long.

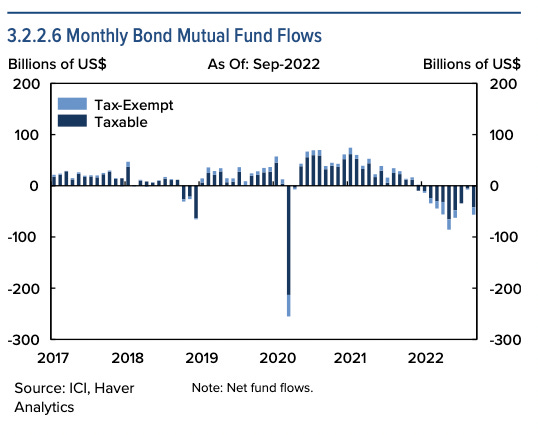

This run dynamic is more likely for a corporate bond fund than other types of mutual funds (those holding Treasuries or equity) because corporate bonds are notoriously thinly traded—often exchanging hands at a rate of once per month—so their prices are more sensitive to selling pressures than are other assets. Potential risks surrounding sudden mutual fund withdrawals have been flagged on both sides of the Atlantic. The ECB's November review of the non-bank financial sector (NFBI, the term regulators prefer over "shadow bank") notes that euro-area high yield corporate bond funds saw outflows in excess of total assets in 2022 by 15% (as of Q3), and large asset sales from open-ended funds could "pose a substantial financial stability concern."8 US regulators highlighted the role that redemptions from mutual funds played in the severe market illiquidity in March 2020 during the Covid-19 Recession:

Procyclical effects

What makes these dynamics problematic is they are procyclical. That really is the theme of this whole exercise. Something causes a bond selloff (e.g., central bank rate hikes and/or the prospect of future hikes), raising financing costs for firms who issue new debt. Investors who own those bonds have less wealth as their prices decrease, so they consume less (the wealth effect). With consumers curtailing spending, companies make less money, so covering their interest expenses becomes more difficult, just as debt financing costs are worsening. This simple exercise in procyclicality is the fundamental (solvency) channel. Moving to technical (liquidity): if investors, whether households, firms, or large institutions, observe the aforementioned fundamental dynamic they may decide holding cash makes more sense than bonds, so they sell debt (perhaps by redeeming mutual fund shares). The act of selling debt pushes down debt prices, further exacerbating the effects, and if you are an investor in an open-ended fund, there is a time element. Getting out sooner is better, and you are able to exchange your entire mutual fund holding on a day's notice. These mutual funds must sell illiquid corporate debt to generate liquidity to meet their liabilities. Now we are entering the technical implications. And it gets worse.

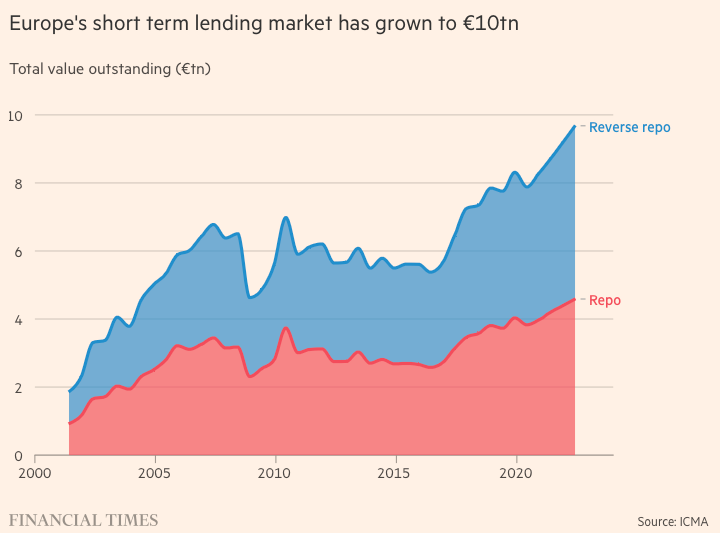

The shadow banking system sources liquidity from a complex web of short-term funding markets, often through repurchase agreements (repos) where one entity sells a high-quality asset to another (usually Treasuries or MBS) with an agreement to buy it back at a specified date for a specified price, with the price difference accounting for the rate of the loan. These markets are large and integral, with at least $6 trillion in repo borrowing outstanding in the US as of 2022Q3, and over $900 billion in daily volume.9 This is not just a US phenomenon, European repo is also growing in size and importance:

Repo markets are a form of secured lending that perpetually reshuffles liquidity across the financial landscape. Money market funds (MMFs) and open-ended funds (e.g., mutual funds) are among the typical lenders in the repo markets, receiving collateral from other entities in exchange for their excess cash.10 This works swimmingly in the status quo and allows for efficient capital allocation. But if mutual fund investors are running for the exits, then they don't have excess cash to lend in repo markets. Therefore, hedge funds and mortgage real estate investment trusts (mREITs) and securities dealers and any other entities who were borrowing from mutual funds yesterday now have to source their liquidity elsewhere. For large securities dealers attached to banks, they turn to the Fed's Standing Repo Facility (SRF) while the hedge funds and mREITs and other players who aren't SRF counterparties turn to the prime brokers (securities dealers) to source liquidity. The rub is whether the prime brokers have the available balance sheet to extend necessary liquidity to shadow banks (e.g., hedge funds) during times of market tumult.

One of the many consequences of the GFC was to roll up the five largest independent dealers into the massive commercial banks (Lehman failed, Bear Stearns to JPMorgan Chase, Merrill Lynch to Bank of America, while Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs became bank holding companies). This move so far appears good for stability but bad for flexibility. Arguably the greatest consequence of the GFC was enhanced financial regulation, specifically for banks, and especially those deemed of systemic importance. One crucial regulatory metric is the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR), a requirement that banks have capital (equity) equal to at least 3% of their assets, or 5% for those deemed to be systemically important. This is a legal constraint on bank leverage, and given the largest securities dealers are part of banks or within bank holding companies, the balance sheet is a scarce resource. Hence activities such as market making are weighed against competing business lines and outstanding obligations that also hoover up balance sheet.

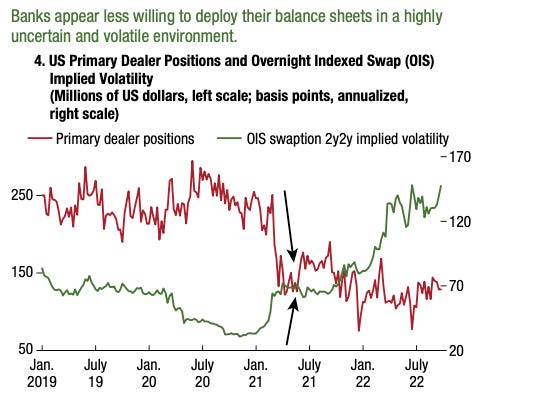

When the mutual fund is fire-selling bonds to source liquidity for redemptions, that probably coincides with general financial uncertainty. Companies are tapping their revolving loans from the same banks needed to make a market for the securities that mutual funds are unloading. Both of these activities consume bank balance sheets as dealers typically fund their bond inventories through the repo markets.11 Beyond balance sheet implications, warehousing securities for future purchase or sale is more risky (costly) for dealers when volatility is higher, as they either have to hedge the risk (which consumes yet more balance sheet) or accept it. We've seen increases in implied interest rate volatility over the past two years coincide with a reduction in security dealer positions (below):

Another post-GFC market structure change is the increase in principal trading firms relative to bank dealers, as technological innovation enables high-frequency trading (HFT). During normal times, HFT is a key source of market liquidity, but these firms prefer to end the day with flat positions and tend to retreat from their market making activities as volatility picks up. This is another example of a procyclical technical impact, as volatility begets volatility.

So far, we've been discussing liquidity and bank-run-like-dynamics with respect to corporate bonds, but that is just an especially vulnerable asset class. These same procyclical reverberations can freeze even the most liquid markets and we witnessed evaporating liquidity in the Treasury market during March 2020. Mechanisms for disruption are nearly the same, however, Treasuries are much more insulated given they comprise the most liquid and cash-like security market in the world. However, the safe haven status of Treasuries mean that when the market ceases to function, the entire financial system becomes dislocated. A troubling theme of 2022 was the erosion of Treasury liquidity:

Treasuries are the world's most prized collateral and the security that forms the basis for the price of all other assets. If you can't correctly price Treasuries you have a big problem. Market disorder during the Covid-19 Recession was so disruptive because at the center was a complete breakdown in the Treasury market. This was due, again to technical (liquidity) channels, as market participants collectively began clamoring for cash in an interstitial period. Treasuries are the most cash-like security in the world, but they aren't quite cash, and in the face of such uncertainty you reduced maturity, and liquidity risks by converting Treasuries to cash.

Without deep-diving the full suite of market mechanics undermining illiquidity in March 2020,12 the point is that the financial-economic landscape is full of heterogenous actors performing a litany of varied functions; however, their risks are fundamentally correlated. Even worse, the causal linkages between them amplify the stressors. The implication is that reduced solvency for one player reduces the solvency for another, and diminishing fundamentals propagate in breadth and depth. Same goes for liquidity. The upshot is that fiscal and monetary authorities (governments and central banks) are the only entities that can step in to correct the feedback loops. Ergo the Fed intervened during March 2020 to backstop the Treasury market and launched a host of emergency programs to provide a market for more risky and illiquid debt instruments. Fiscal policy supplied historic bridge financing in the form of PPP loans. These, and other emergency policy responses prevented a full blown financial crisis in 2020.

Pension funds are shadow banks

We explored shadow banking in the form of open-ended investment funds, but many other non-bank financial firms have characteristics of shadow banks. Pension funds are among the world's largest institutional investors and invest pools of capital to pay out future liabilities (pensions) to plan participants. It is easy to envision a run on a bank, or a run on a mutual fund, but the idea of a run on a pension is ambiguous as plan participants cannot withdraw their assets on a whim. But we saw in the UK that a run on pensions can occur, via technical (liquidity) channels.13 UK pensions had massive derivatives positions to hedge their interest rate exposures which suddenly lost value during a historic gilt route precipitated by the enigmatic Truss government's mini-budget. As gilts violently sold off, the pensions received margin calls from their clearing brokers (you settle futures gain-loss daily through variation margin), forcing them to liquidate assets (often gilts) to source the liquidity, applying more downward pressure on markets, driving interest rates higher, and causing the derivatives to lose more money. The BOE (rightly) intervened to break the causal chain of selling pressure.

In this way, sudden market moves and psychology shifts can turn a stable environment into one with runs on unsuspecting entities. This is why the abruptness of interest rate increases matters. Had 10-year UK gilt yields gone from 3.17% to 4.54% over the course of a quarter or a month that would be a large move, but one that the market mechanisms could handle (i.e., pensions can meet margin calls in an orderly, serial fashion). To use our lingo, the effects would be felt more through the fundamental than the technical channel. But given this move happened over the course of a week (9/20 to 9/27) last year, market plumbing was insufficient to withstand the abrupt shift to higher interest rates. Adding to the problems, the electronic systems of some banks were unequipped to handle the heavy traffic (I'm looking at you Northern Trust). The volume that markets can endure is largely a product of their underlying liquidity.

Market Liquidity

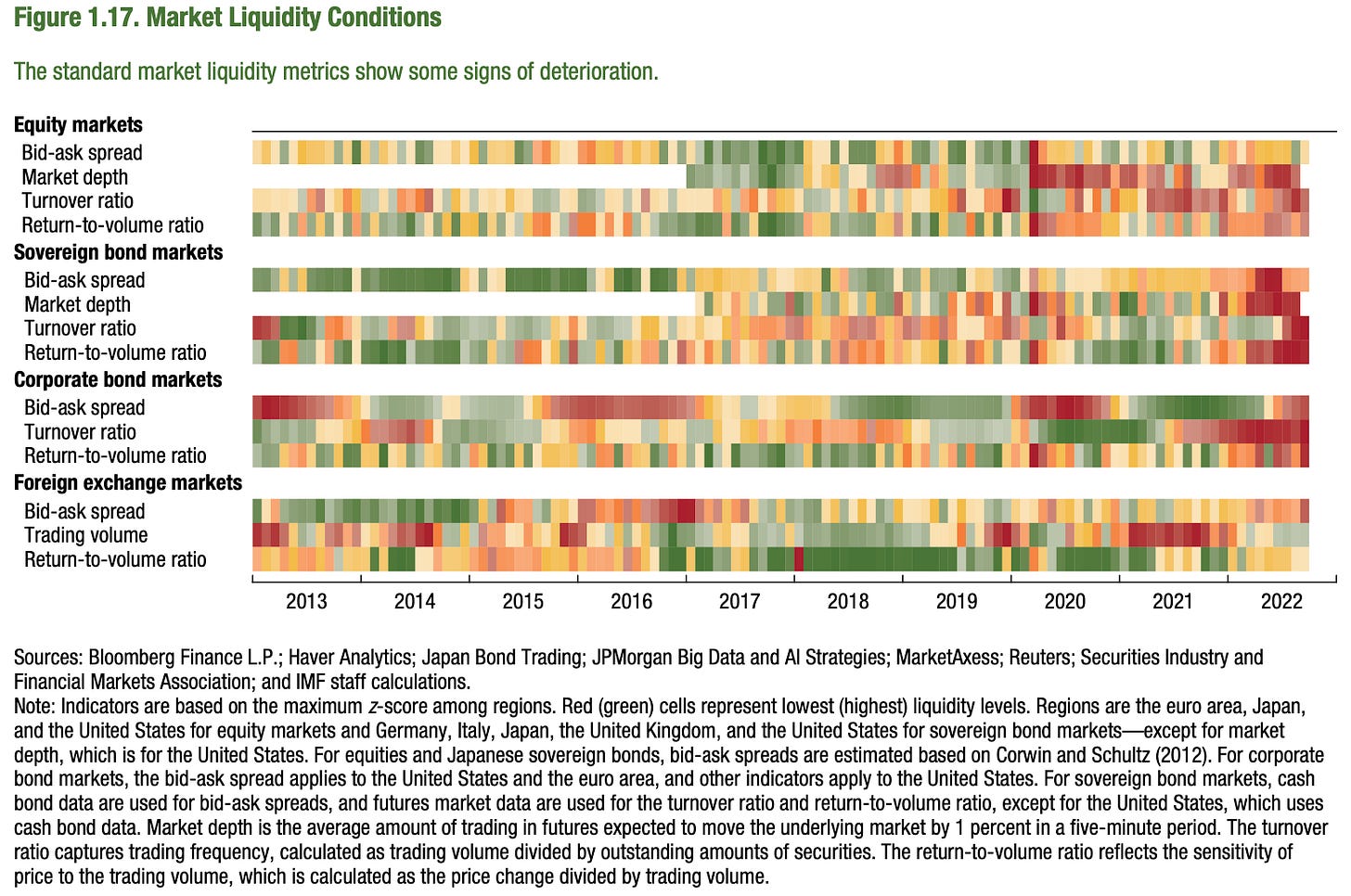

When market liquidity is poor, volatility increases because the trading volume required to engender a price swing is lower. If you are a motivated seller, you are forced to accept the price offered to you, even if it is far below the previous price. When volatility swells, liquidity deteriorates as dealers increase bid-ask spreads, reduce inventory, and/or step back from the market. It's yet another feedback loop. A hallmark of 2022 was deteriorating liquidity across all asset classes:

Hedge funds and insurers are also shadow banks

The shadow banking landscape is wide, complex, largely unregulated, and without a public backstop. Any financial entity with the potential for abrupt changes in short-term liabilities due to changing financial conditions could theoretically experience a run. We already mentioned a few examples, but hedge funds are entities that often operate highly leveraged portfolios using short-term funding, typically via repo. Any change in funding availability could make liabilities difficult to meet during a market stress event (e.g., settling derivatives gain/loss). Life insurers are another segment of the ecosystem that could be stressed by a sudden rate move. Profitability tends to rise with interest rates as life insurance liabilities are usually higher duration than assets, however, increasing interest rates incentivize clients to surrender their policies for cash, and doing so creates a current liability for the insurers. There is a risk that an abrupt rise in interest rates will cause a sudden increase in surrendered insurance products as customers withdraw savings early. To meet surrenders life insurers may have to sell assets at depressed levels which would cause losses, and as we've discussed, these events don't occur in a vacuum. The insurer will be scrambling for liquidity at the same time the pension manager is selling assets to cover losses in their derivative hedges, amplifying the sell off. If you are still doubting the complexity and interconnectedness of the shadow banking system, the below schematic makes the point:

Households face interest rate risk

We've discussed debt markets at the corporate and sovereign levels, but another essential component of this fractal web is the household level. For individuals, the vast majority of debt is issued via mortgage. Just like firms, the terms of the debt are important. If you have an adjustable rate mortgage, or a short-term fixed rate mortgage, the abruptness of the rate rise and the time spent at that higher rate are hugely important. For much of the globe, variable rate mortgages or fixed rate mortgages lasting just a few years are the norm. For folks in this situation, rising rates will engender a large increase in monthly liabilities. At the macro level, countries with more household leverage and more interest rate sensitivity will suffer deteriorating household fundamentals. Of course these impacts cascade through economies as reduced consumption means less revenues for corporations.

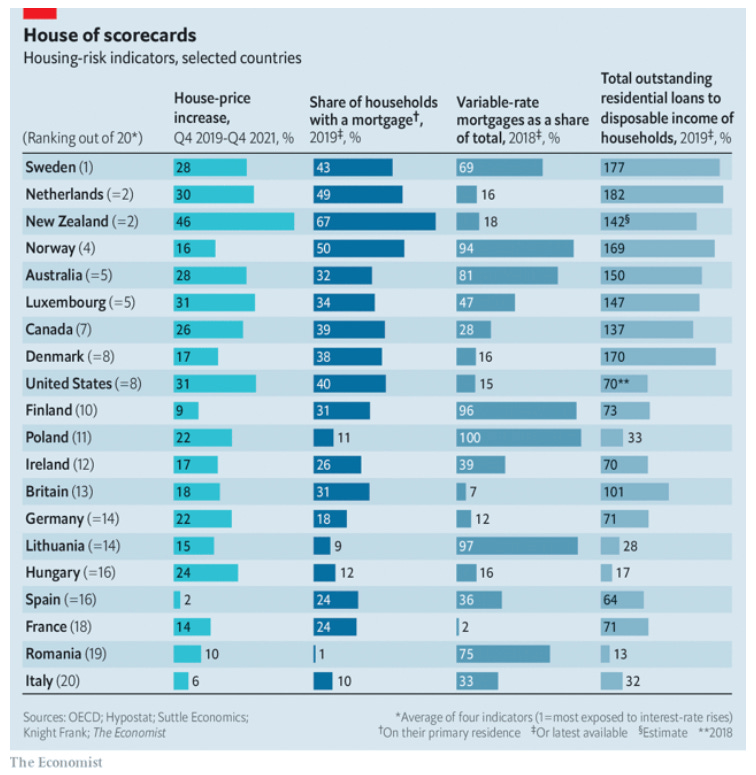

You guessed it: the housing industry is procyclical so slowdowns in the sector will spillover to others. Higher financing costs coupled with slowing economies are a recipe for falling housing prices, disincentivizing construction, and upping the cost for financing home improvements.14 This burden will be disproportionately shared across the world:

Rising rates are especially bad news for countries like Australia and New Zealand where over half of all residential mortgages will reset at higher rates in 2023. In the UK about 40% of mortgages will have higher rates next year, and 20% of households may face payments that are up £5,000 a year by the end of 2023. The housing market is expected to slump but generally remain robust, and again, rates will be a key determinate of how much stress is exerted on the world's largest asset class.

The US is in an enviable situation as a country that subsidizes mortgages to allow 30-year fixed terms to be the norm. Nearly two-thirds of total US mortgage debt was securitized into MBS as of 2021, with essentially all occurring by way of the Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—which have been in public conservatorship since 2008—or Ginnie Mae, which guarantees MBS created via mortgages insured by various federal agencies (these are the OG shadow banks).15 This system allows for the bifurcation of mortgage origination and investing. Origination is increasingly handled by non-bank mortgage providers (shadow banks) rather than the giant US commercial banks, and is backstopped by the GSEs. US households have deleveraged since the GFC, the Fed is established as a buyer of last resort for MBS, and the GSE mortgage banks ensure households can secure long-term, fixed financing. Altogether, this means that US households are significantly less sensitive to rising rates than other nations. But the nodes connecting mortgage origination with MBS investment are rife with shadow banking entities, so abrupt interest rate changes could disrupt financial intermediation (we've already seen some mortgage originators fail as home buying slows).

What it means

Everything we've discussed to this point can be and has been corrected in the past by central banks. They are the lenders and market makers of last resort. When something began breaking in the UK last fall, the BOE stepped in to cauterize the gilt selloff. The Fed will do the same if the Treasury market gets sufficiently stressed. But the uniqueness of this environment is that central banks are likely more hesitant to intervene now than they've been at anytime over the last three decades.

The thing that separates a financial system that works and one that doesn't is the confidence participants have in it and the contracts with their counterparties. Our biggest counterparty is the Federal Reserve because the money we use (our asset) is their liability. Core to the Fed's credibility is meeting its inflation target. Given the importance that the amorphous concept of confidence plays in the system, you could argue that the Fed's most important job at the moment isn't bringing inflation back down to its 2% target, but keeping us confident that it will do so. The Fed continues to talk about the dangers of inflation expectations becoming unmoored (i.e., we lose confidence in the Fed's ability) so coming across as a credible monetary authority with a singular focus on inflation is of paramount importance.16 (I am personally skeptical that inflation expectations matter as much as the financial media, central bankers, talking heads, and people at CFA dinners think they matter, but that is a topic for another time.)

Intervening in asset markets to provide liquidity is a pause on the tightening activities that are part of the puzzle to curbing inflation. If a central bank is buying assets while hiking interest rates, it is saying "yes" while shaking its head "no." Doing so is completely defensible and necessary if firms that are otherwise solvent are temporarily endangered by market malfunction. Such an event would increase the public relations tightrope for central banks as they must continue to affirm the tightening stance while explaining why markets needed intervention, and that their actions didn't expose a vulnerability. This whole exercise is full of circulars because the Fed is one of the key agencies (along with the OCC and FDIC) tasked with the regulation and supervision of the banking industry, while it is simultaneously responsible for setting interest rates and the daily market transactions required to implement monetary policy (Open Market Operations). If a policy decision from the Fed causes something to break, well the Fed ought to have known that would happen, the "market" will say, because the Fed is the one setting the policy and regulating the financial system that is implicated in its monetary policy decisions. By deciding the appropriate level of interest rates, future rate increases, and the messaging of those ideas, the FOMC carries the strategic initiative and should have the best knowledge of the impacts on the banking and shadow banking systems (as it supervises those systems). If something breaks, the Fed is also the entity that cleans up the mess, and depending on the proximate cause, they are likely to be ridiculed rather than thanked. The market/public/politicians will say; 1. You ought to have known those rate hikes would be more than the system could handle; 2. You failed in your ability to regulate the financial apparatus because you had to bail it out, again; 3. You have too much power in your role as pyrotechnic and fire brigade, and your powers should be reduced; 4. You are ineffectual and come to think of it, a central bank is un-American. These are increasingly stylized but there is at least some truth to all of them.17 The point is that the Fed is in a tough place because it doesn't want accusations of overtightening, yet inflation in excess of 7% is even more intolerable. By contrast, the BOE's decision to buy gilts as pensions were hit with increasingly burdensome collateral calls was an easy one since they didn't spark the fire. With the market and media assured of the culpability of Trussonomics, the firefighters couldn't be simultaneously accused of arson.

A higher level of interest rates impinges the budgets of households and constrains the profitability of firms. Those who are overextended will go under as the economy slows and that is par for the course in an economic tightening cycle. But an economy that is resistant to tightening with both stubborn inflation and high employment (you know, the things we are currently experiencing) will require some combination of more rate hikes and a longer period of higher rates to bring inflation down to tolerable levels. Like acclimatizing to a higher elevation, level, abruptness, and time are all important in determining how interest rates will stress the fundamentals of the economy as well as the underlying systems that efficiently allocate capital. Risks are not only correlated for firms, households, and financial intermediaries but are causally connected. We will find out if we've been acclimatizing or deteriorating.

A hallmark of financial dislocation is the disruption of a known weak point that propagates further and faster than anticipated. We discussed only a small subset of the myriad of financial linkages and how their associated risks might amplify throughout and within the system. Expect markets to remain on edge until we have a clear path to inflation that central banks can tolerate,18 and by extension, a return to rate cuts, are in sight. Watch out for a further deterioration in liquidity, specifically in high-quality fixed income markets, and heightened volatility in those markets. We've seen some alternative asset managers limit withdrawals recently, showcasing issues meeting liabilities, and mortgage lenders are beginning to fail. These are most likely isolated pockets of dysfunction rather than spreading problems, but they do merit watching.

Read Jon Krakauer's infamous Into Thin Air if you are interested in a firsthand account of these effects

The result is business are more discerning with new projects (reduces demand at the aggregate level of the economy) and hiring (also reduces demand and upward pressure on wages). With higher debt servicing costs some businesses are forced to cut costs and will turn to layoffs which cause unemployment to rise (reduces aggregate demand and income). With less aggregate demand from business investment and household consumption firms are making less money, so the impacts are self-reinforcing. And so on and so forth

Pinning down the prevalence of zombie firms is highly dependent on the assumptions used to define a zombie. A few years ago a BIS report reckoned that zombies accounted for 2% of firms in the late 1980s and 16% by 2016. However, the Fed counters that zombies are overcounted, and if you exclude firms that are growing, their ubiquity is in the high single digits, relatively unchanged over the past two decades, and not a systemic risk to the financial system

Junk bond default rates in the US remain low at less than 2% in 2022 , below the long-term average of 3.8%, after exceeding 5% in 2020 (the highest since 2009). Companies are broadly expected to fail to pay their debts at higher rates in 2023 and 2024, roughly in line with long-term averages. Others think a proliferation of zombie firms could lead to defaults in excess of 15% amid a severe recession scenario

Investor appetite is increased of late and a bevy of firms are scrambling to secure financing due to some combination of urgent necessity and concern that markets erode further

More technically, banks expand the money supply by issuing loans (assets) against their deposits (liabilities). The theoretical expansion of the money supply due to bank loan issuance is the reciprocal of the required reserve ratio (the portion of deposits that banks are required to hold as reserves). In the US the Fed cut the required reserve ratio for the largest banks from 10% to 0% during the Covid-19 Recession where it remains. Although banks are allowed to issue the entirety of their deposits as loans (the theoretical money creation due to bank lending is thus infinite) they continue to hold excess reserves at the Fed due to a combination of business and regulatory factors

Depending on the type of fund, that could be investment grade, high yield, leveraged loans, CLOs, ABS, private credit, or some combination thereof

ECB. Financial Stability Review . November 2022. page 71

Financial Stability Oversight Council. 2022 Annual Report . Pages 28-31

FSOC. 2022 Annual Report. Page 30

FSB. Liquidity in Core Government Bond Markets . 2022-10-20. Page 9

Josh Younger's description on the Odd Lots podcast is a great place to start

In a structural sense, a pension is essentially short Treasuries (it benefits when interest rates rise) because its liabilities are measured on a present value basis, so the liabilities of the pension rise when interest rates fall, and if its assets don't rise with the liabilities, its funded status falls. To prevent being buffeted by interest rate volatilities, pensions often hedge their interest rate risk in what is called liability driven investing (LDI). If the pension isn't fully funded (most aren't!) you need to use your assets to return some positive amount that brings their value in line with the present value of your liabilities and you need to hedge the interest rate risk (ensure that your assets have the same duration of your liabilities). Positive return potential and interest rate exposure both require balance sheet, so pensions will use derivatives to generate the required exposures

A home equity line of credit now has a higher interest rate and the amount the bank is willing to extend is smaller given a reduced home value

Ginnie Mae is a pure public entity, while Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are quasi-public, and together they purchase loans from mortgage originators and package them into MBS which are sold into the $11 trillion US MBS market, of which $300 billion trade every day

Part of convincing markets that central banks are serious about getting inflation under control is reversing the post-GFC accommodative policies, thereby shrinking balance sheets. In the current iteration of QT (allowing securities to mature as opposed to selling securities on its balance sheet) the Fed isn't shrinking reserve balances but reducing the Treasury General Account (TGA) liability, so the impact is to remove a marginal buyer of government debt (interest rates rise) as opposed to draining the monetary base (reduction in available money in the banking system). The Fed began QT in June of last year and all other major Western central banks are doing likewise (except the BOJ)

I could believe number 1 depending on the circumstances; number 2 is a half-truth at best (as Congress grants the Fed its regulatory powers and largely sets the parameters); and I would disagree with 3 and 4, although there are kernels of truth within them, and they do play upon the priors of many

Even this is an inscrutable question. Would the Fed continue tightening to bring inflation down from 3% to 2%? I highly doubt it if the underlying fundaments of the economy are materially worse (i.e., U-3 unemployment is above 5%) but we just don't know how stridently central banks will work to achieve their policy targets once the high inflation (not a technical term, probably defined as over 4% ) is behind us