What happened

Changes usually occur in the wake of crisis. Political reform and sovereign reorganization followed WWI with the creation of the League of Nations and several treaties that remapped swaths of the globe. Economic and political reform followed WWII with the rebuilding of the League of Nations into the UN and the creation of Bretton Woods—birthing the IMF and World Bank—to define the new globalized economic and security structure of the West.1 Monetary policy reform resulted from the Great Inflation period of the 1970s and early 1980s as the Fed discarded its gradualism playbook to aggressively hike rates as central banks learned the importance of credibility and many reaffirmed their independence.2 Accounting scandals during and around the 2001 recession led to the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which improved disclosure and audit standards. A raft of reform followed the Global Financial Crisis via the Dodd-Frank Act to shore up the US financial system and establish household safeguards via the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection. One thing that these changes have in common is they are top-down, dictated by centralized actors and institutions.3 The aftermath of the Covid-19 recession may be different in that lasting changes will be determined in bottom-up fashion, an aggregation of changes in behaviors and preferences.

In the immediate reverberations of the pandemic, there were myriad prognostications of how society would change. We would never go back to offices. We would all move to the Sun Belt. We would buy everything online. We would spend more time online, playing video games and populating the multiverse. James Altucher even pronounced New York dead forever (and there was a time where that was sort of believable!). And the stock market began reflecting these changes during 2020 and 2021. A common thread of this new reality is the technology required to support behavioral changes auguring increased digitization in all aspects of our lives. In the post-Covid world, we would be consuming more computers, more video game consoles, streaming more video, and properly outfitting our home offices and classrooms. Of course, the world was always becoming more digitized, but the immediate collective reaction to Covid-19 sped that up. In fact, the pandemic seemed to speed up many trends already underway (i.e., hybrid work environments, ecommerce, video games, food delivery, virtual communication). The functioning of this new reality all relies on semiconductors, the physical underpinning of digitization. Semiconductors are the building blocks of the most exciting technologies on the horizon: progress in machine learning, autonomous driving, smart contracts and digital assets, robotics, metaverse, AI drug discovery, among others. They also provide core functions to all the current technologies we take for granted, from our vehicles to appliances (IoT) to electronic storage (cloud and local) to screens and visual effects.

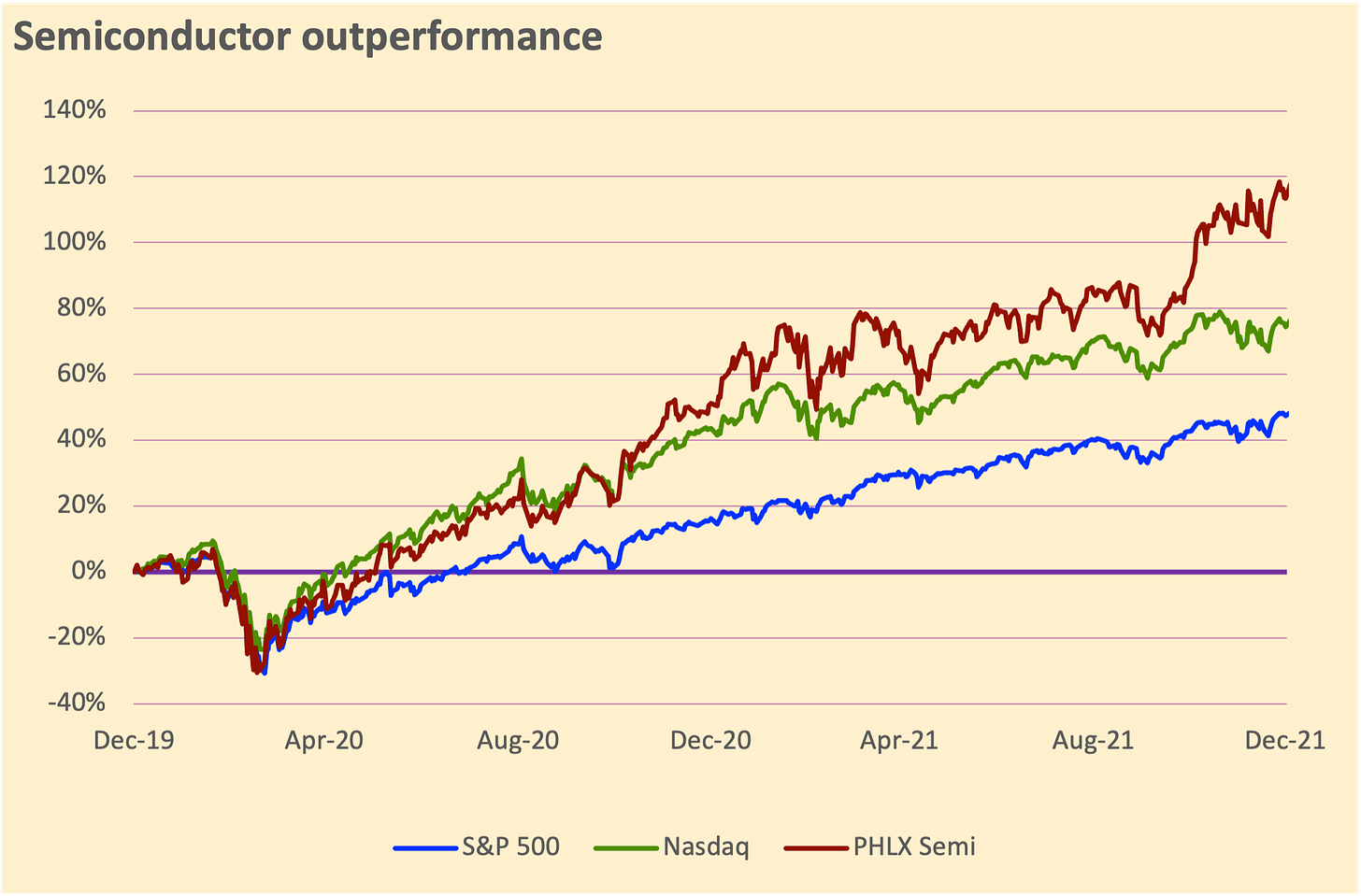

Technology stocks dramatically outperformed during the pandemic, with semiconductors among the top industries in 2020 and 2021. The Philadelphia Semiconductor Index returned 51% in 2020 and 35% in 2021. This bested technology returns over each period as the Nasdaq Index returned 48% in 2020 and 26% in 2021, and easily topped the broad market as measured by the S&P 500 Index (18% and 29%). See below if you are a visual learner:

Source: Yahoo Finance. Cumulative performance indexed to 12/31/19

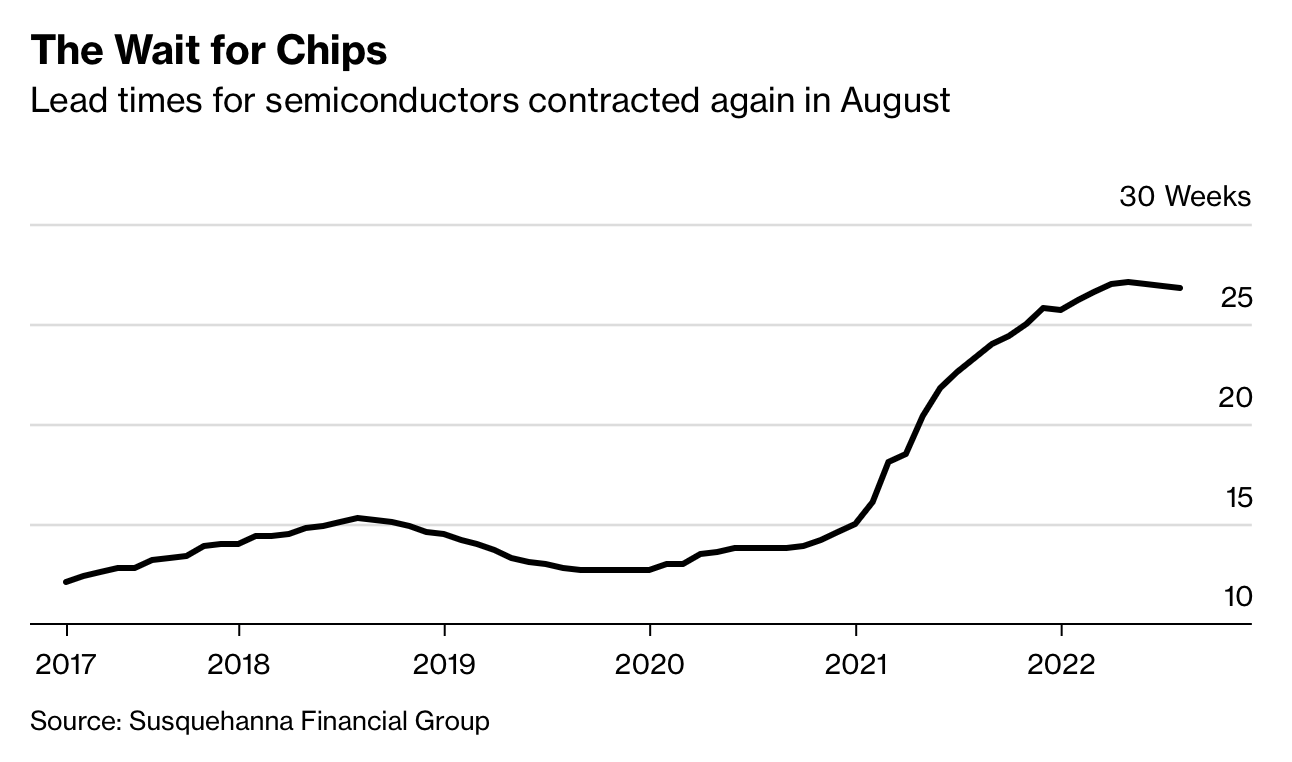

These returns weren't all market exuberance, as technology demand spiked due to lifestyle alterations during the pandemic. Among the most stark behavioral changes was the transition from spending on services prior to the pandemic to spending on goods.4 Technology in the form of computers, servers, phones, game consoles, crypto mining rigs, appliances, and vehicles, were among the litany of those goods. The demand for chips jumped as a result. Supply chain woes have been a prominent post-pandemic story and material contributor to inflation. One of the first areas to see dislocation was chips. Charts like the one below kept surfacing, showcasing both the degradation of global supply chains and the insatiable demand for semiconductors.

Source: Bloomberg, 2022-09-08

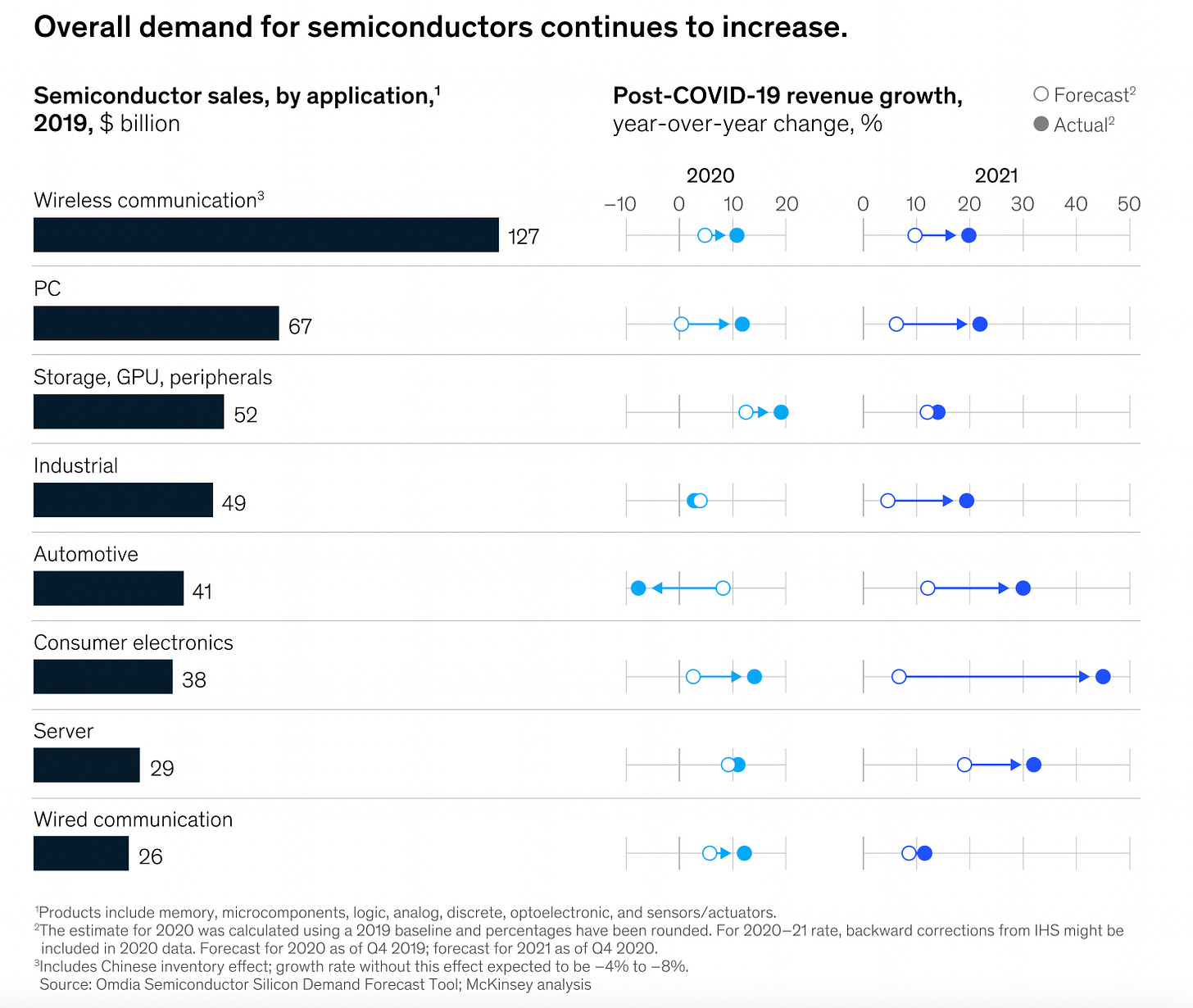

Companies took the hastened digitization message to heart. They saw the demand spike for things like PCs and figured we were on an entirely new consumption trajectory because the world had changed. The only commuting of the future would be telecommuting. This wasn't just a bad case of motivated reasoning among semiconductor executives—their firms received a deluge of orders! Revenues topped estimates in 2020 and 2021, underscoring the continued demand in all segments. Here's a useful illustration from McKinsey:

Forecasting demand is notoriously difficult. One thing that stands out in the above graphic is that automotive and industrial revenue growth contracted in 2020, with automotive down nearly 10%. The travails in procuring chips for automakers is a microcosm of the supply chain indigestion the global economy suffered in the post-Covid epoch. The story goes something like this: When the pandemic hit in the spring of 2020 demand plummeted amid a wave of consumer and business uncertainty. Automakers scrapped their orders for fear of a glut and were then caught off-guard when consumers began purchasing durable goods (like vehicles) at record rates. Car companies responded, as expected, by rushing to ramp up production. But the problem is that producing a car is a lot more complicated than flipping a switch at your factory. When the production is halted it takes time to get factories running again, both in the sourcing of inputs and the organization of labor. Labor became more difficult to come by due to a reduction in the work force and the aftershocks of the pandemic as infections could upend productivity. And the entire automotive supply chain was confounded by the "just-in-time" ordering process where components orders are synchronized with the production schedule to reduce inventory costs.5 This is a nice way to be capital efficient during normal times but meant carmakers had perilously low inventory as demand recovered. In autos, chipmakers have been catching up ever since, as evidenced by "The Wait for Chips" graphic. Supply chains have yet to recover! There is a term for this dance between demand and production—the bullwhip effect—elucidated by Luke Templeman at Deutsche Bank:

The bullwhip effect occurs when a drop in customer demand causes retailers to under-stock. In turn, wholesalers respond to a lack of retail orders by under-stocking themselves. That then causes manufacturers to slow production. Eventually the reverse occurs. As customer demand comes back, retailers quickly order more goods, often too much, and wholesalers and factories are caught short. Once shortages occur, prices increase. Eventually production ramps up at levels that are far beyond equilibrium levels and this cascades down the chain. These violent swings in availability of goods then continue back and forth until an equilibrium is eventually established.

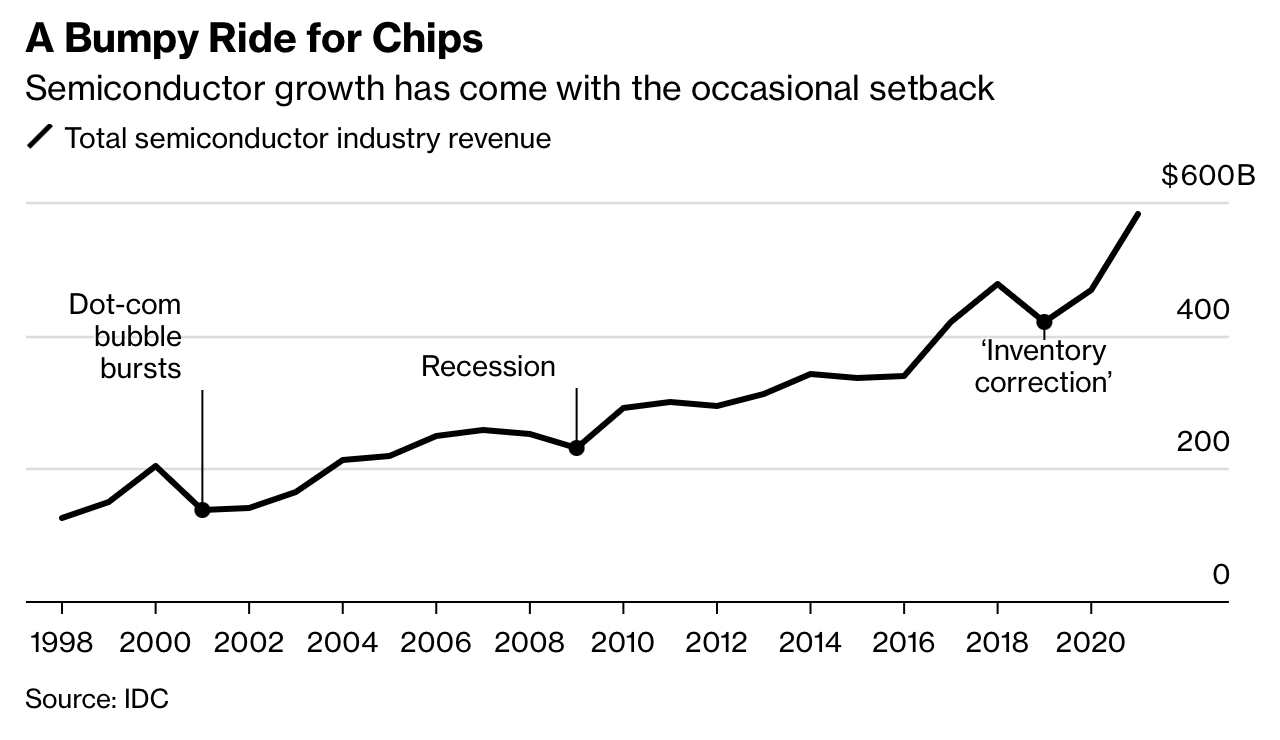

You'll notice that the path to equilibrium among the bullwhip is an overreaction from production that outstrips demand, leading to a temporal glut, before ordering can appropriately react. We've seen some early signs of that behavior in autos with manufacturers reportedly ordering enough vehicle chips in 2022 to outfit 120 million new cars while sales forecasts see demand for 83 million. Historically, the semiconductor industry has been highly cyclical, marked by periods of supply-demand imbalance, either due to slacking demand as occurred during the 2001 and 2008 recessions, or overproducing as materialized in 2019:

Source: Bloomberg

The jump in digitization materialized as the semiconductor industry posted record revenue in 2021 with aggregate sales in excess of $500 billion. Some estimates reckon that semiconductor revenues exceeded the smartphone industry last year.6 The industry was rightly ebullient to begin 2022:

Global chip sales rose 25% in 2021 from the prior year to a record $583.5 billion, according to research firm Gartner Inc. Factories working round the clock couldn’t keep up with demand. Prolonged shortages are projected to boost the semiconductor industry’s revenue by 9% this year, Gartner said, outpacing the historic average rate of growth.

- Wall Street Journal, 2022-01-30

And predictably this growth prompted capital expenditure and upped production across the industry. Firms in the foundry and integrated device manufacturer (IDM) space poured money into new fabs, and fabless chipmakers upped their orders. Perhaps the demand would be strong enough to prevent a cyclical lull. This excerpt from early 2022 appropriately captured the mood:

Last week, Samsung Electronics Co. expressed confidence the good times would continue for its memory-chip business, assuming component shortages and supply-chain challenges didn’t get in the way. Intel Corp. CEO Pat Gelsinger, after the company reported record sales for last year, said “2022 will only be better.”

And here is a quick overview of what expansion plans for the industry looked like to begin the year:

On January 13th Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s biggest contract manufacturer, said it would spend up to $44 billion on new capacity in 2022. That is up from $30 billion last year, triple the number in 2019 and ahead of earlier plans to spend over $100 billion in total over the next three years. Intel, an American rival, plans to burn through $28 billion this year. On January 21st it said it would build two big new factories in Ohio by 2025 at a total cost of $20 billion. An option to build six more later would take the overall price tag to $100 billion. Samsung of South Korea, TSMC’s closest technological rival, has hinted that its capital spending for 2022 will surpass last year’s $33 billion. Smaller firms, such as Infineon in Europe, are also splurging.

Politicians took notice of the dearth of chips. Not only could firms not source sufficient amounts of chips, but attention to the global semiconductor industry brought some geopolitical concerns into view. This topic could be its own newsletter so we'll try to keep it concise. Last week we talked a bit about deglobalization trends ensuing Russia's offensive in Ukraine. Friend-shoring, where companies and countries more carefully consider where components and inputs come from, is coming into focus. This is opposed to the prevailing adage of the globalized second half of the 20th century—source from the lowest cost at all costs. The fragility of inputs at the country and company levels is now under intense scrutiny. Well, there is a version of this in chipmaking, and it centers around Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

TSMC is both the purveyor of the foundry model in the late 1980s and the world's preeminent foundry. The advent of the foundry model allowed the industry to move from vertical toward horizontal integration, enabling firms to focus more on niche products. A foundry is a contract manufacturer, allowing one company (such as Nvidia or AMD) to specialize in the design of semiconductors and another (TSMC, also Samsung and Global Foundries) to actually manufacture them. The physical production of leading-edge wafers is mind-numbingly complex and capitally intensive, and the genius of TSMC is to allow other firms to outsource that complexity and associated capital expenditure (to TSMC and equipment makers like ASML, Lam Research, etc.) which keeps Moore's Law alive.7 Setting up a fab takes several years and costs around $10 billion. TSMC allows technology giants like Apple, Microsoft, Google, and the company formerly known as Facebook to design their own highly sophisticated and specialized chips, without having the know-how to actually make them. TSMC produces chips for all those companies.8

This arrangement has worked great for the semiconductor industry (chipmakers, equipment-makers, and foundries like TSMC) and consumers. The fly-in-the-ointment is that the “T” in TSMC refers to the island off the coast of China that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) claims is within their sovereign purview while the West (and Taiwan!) believe it is independent. Russia's bellicose actions makes envisaging a Chinese invasion of Taiwan feel plausible. If a war metastasized on the Taiwan Strait the economic consequences would be dire. The UN estimates that shuttering TSMC's facilities would reduce global GDP by $1 trillion per year.9 And that could be a massive understatement with some experts warning that removing TSMC from the world stage could setback the global trajectory of technology advancement by a decade.10 To just bring the point home, it's estimated that 70% of all chips made worldwide pass through Taiwan on the frontend (production) or backend (packaging).11

These geopolitical considerations, coupled with the shortages, and the ongoing technology race with China, prompted lawmakers to pass The Chips Act in 2022 to provide $52 billion in grants and incentives for US semiconductor manufacturing, and $39 billion in financial assistance to build fabs. The Chips Act incentivizes friend-shoring with provisions that bar subsidies if the company is building advanced plants in China or other countries deemed less-than-friendly.12 Further government action in August upped export controls of high-end chips to China as the world's two largest economies vie for dominance in tech and AI.13 And two weeks later further guidance was provided to equipment manufacturers that new rules would ban the export of tech to produce 14-nanometer or lower (more advanced) semiconductors to China. That ban was implemented on October 7, preventing equipment export to Chinese chipmakers without first obtaining a license, and expanded export controls to firms on the Entity List via the Foreign Direct Product (FDP) Rule.

These controls are intended to keep sophisticated chips out of reach for the Chinese military and firms with military ties or a spotty humanitarian record—there are currently 28 Chinese firms on the Entity List for these sorts of reasons—and prevent China from developing the capacity to create sophisticated chips in its own fabs. (China is historically inept at creating cutting edge chips.)14 Updated regulations mean immediate consequences for US and global firms since China is a huge market for semiconductors:

While many chipmakers, foundries, and equipment markets have high revenue exposure to China, they are impacted differently by the new rules. Qualcomm tops the above chart of revenue exposure but its business will be less affected since the chips it makes are used in mobile phones and telecommunications equipment. The export rules aren't intended to choke access to semiconductors writ large, but affect a specific subset of semiconductors and a subset of users and their construction. Similarly, Texas Instruments' products are used in automotive and industrial applications, and none are cutting edge, so they won't be impacted. The chipmakers affected by this rule—Nvidia and AMD—create specialized GPUs that are integral in AI applications. China is a relatively small market for equipment makers (like ASML), but the new rules are immediately felt for such firms:

One large supplier of chipmaking equipment, ASML, told US employees to stop installing or servicing equipment at any Chinese chip factory while it sorts through the new rules. Another equipment provider, Applied Materials, said the export restrictions will prevent it from making sales of roughly $400 million in the fourth quarter.

We described how chipmakers bolstered production in the wake of the pandemic as consumers and businesses splurged on technology of all types. Some of that demand is drying up this year as consumers revert toward pre-pandemic behavior patterns and feel the bite of generationally high inflation. Their spending patterns follow those behavioral changes, as the real spending on services in the US is up 2.2% YTD, while goods spending is down slightly YTD (aggregate goods spending in real terms peaked in spring 2021).15 If you thought that some of the post-Covid expectations were looking too rosy, and we might see the other side of the bullwhip, well here you go:

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang confirmed what we’ve suspected for months: Nvidia actually built too many gaming GPUs and is now being forced to sell them for less money. “We found ourselves with excess inventory,” says Huang. “Our strategy is to sell-in well below the current sell-through levels in the marketplace to give the channel an opportunity to correct.”

- The Verge 2022-08-24

We were also reminded that trees don't grow to heaven, and consumers weren't going to purchase PCs at the 2020 and 2021 rates forever:

Demand for personal computers is falling by its fastest pace in nearly a decade, as economic turbulence roils the market after a two-year boom in pandemic-driven purchases. Shipments in the second quarter dropped by 12.6% from the year-ago period, marking their steepest decline in nine years, according to data from research firm Gartner Inc. The company says computer makers dispatched 72 million PCs in April through June, down from 82.4 million the year prior.

- Wall Street Journal 2022-07-11

Chipmakers with exposure to that market are getting walloped. Intel's 2Q results were grim with a surprise net loss of $454 million, and revenues down 22% to $15.3 billion.16 The firm blamed a slowing economy and supply chain issues, while also cutting its forecast for PC sales. Nvidia and AMD face dual exposure to both the PC market and supercomputing applications within China. Their chips are also used in crypto mining and with the prolific selloff in digital assets many miners have put their rigs on the market, adding to the sudden availability of GPUs. The new export rules and a slowing economy served to reset their expectations:

Nvidia, the world’s largest chipmaker by market value, said Wednesday that new US rules barring the sale without a license of the advanced chips to Chinese customers would cost it $400 million in sales. It said it may have to transition some of its operations out of China.

- Wall Street Journal 2022-09-01

And:

AMD's preliminary third-quarter sales missed projections by more than $1 billion, adding to concerns about the sputtering market for personal-computer chips and sending its shares sliding in late trading.

- Bloomberg 2022-10-06

Coincidentally, the stock of Nvidia and AMD are both down 63% YTD. Nvidia entered 2022 with a pricey valuation, sporting a a price-to-sales ratio of around 25, juxtaposed to a price-to-sales ratio on the S&P 500 of about 3. That valuation, along with the share price, has drastically retreated throughout the year. Most of that change was a revaluation story with the market undergoing a repricing of future cash flows with rising interest rates, a dynamic we've mentioned before. That is, it was a valuation story until Nvidia announced 2Q earnings on August 24 with non-GAAP EPS down 51% YoY and 63% below the previous quarter, missing consensus expectations by 60%.17 After growing revenues for eight consecutive quarters, 2Q revenue fell 19% QoQ, but remained slightly positive YoY. Nvidia's valuation to begin the year, and that of many semiconductor firms, was predicated on a secular growth environment propelled by rapid technology growth and innovation. That story ended in the second half of this year.

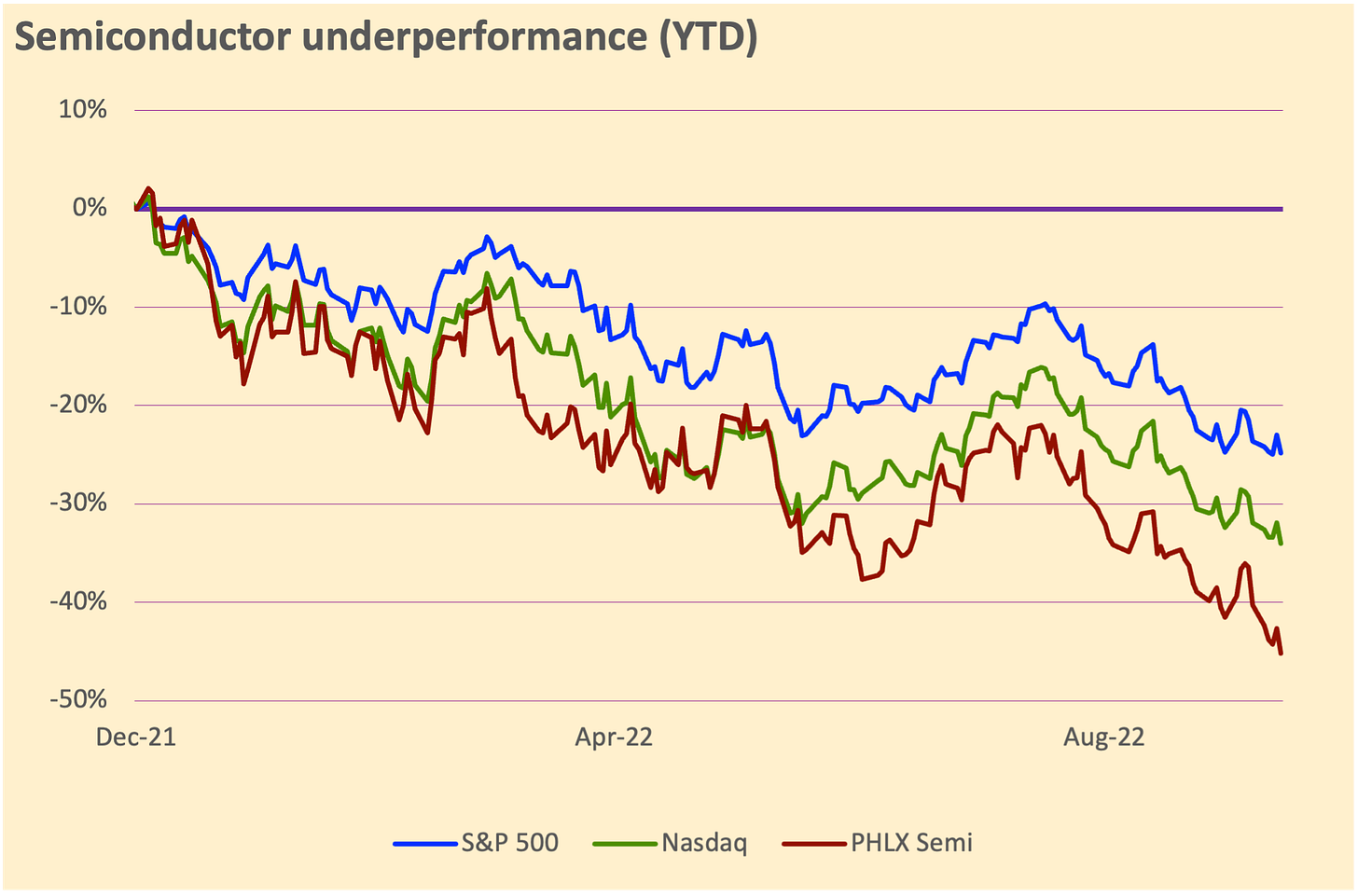

This newsletter began with a chart of semiconductor outperformance throughout 2020 and 2021, and the story of 2022 is quite a bit different. Taking the cumulative performance of the three below indices since the start of 2020, the results have converged with the S&P 500 trailing the Philadelphia Semiconductor Index by 6% and the Nasdaq trailing the chip benchmark by less than 2%:

Source: Yahoo Finance. Cumulative performance indexed to 12/31/21

What it means

The market continues to find pricing stocks difficult in 2022 given the backdrop of global inflationary pressures and associated monetary tightening used to bring price growth back to acceptable levels. These impacts hitherto caused broad cuts in equity valuations while earnings remain resilient. Earnings growth expectations for 3Q at the S&P 500 level has been progressively slashed since the end of 2Q, but is expected to remain positive YoY.18 If you think that earnings remain positive from here on out, stocks are a buy. If you think earnings capitulate as the economy fails to fend off recession, well, there will be more pain. And the complicating factor here is the trajectory of monetary policy. If you do get earnings contraction, recession, and disinflation the Fed probably says "Alright, we are putting rate hikes on pause and watching the data very closely." Such a policy pivot would be good for stocks, and elucidates the difficultly in broad market pricing right now.

If you are an investor that can stomach volatility, certain sectors are compelling because of the favorable growth ahead. In a few years, a few down quarters will likely be of negligible impact. Semiconductors are one of those sectors, because—as we said at the top—they are the building blocks for all digitization and technology innovation trends. We're already getting some earnings capitulations from certain companies in the space, but the long-term trends remain intact. The semiconductor complex now features much more reasonable valuations than when the year began. A best-in-class company like TSMC19 became much cheaper:

Source: Bloomberg 2022-10-13

TSMC is in a league of its own in terms of ability to build the world's most sophisticated semiconductors and is among the world's most strategically important companies. Right now, on a P/E basis, the powerhouse is trading at the cheapest level since 2015 and its shares are down 47% YTD. TSMC announced 3Q earnings on Thursday, October 13 and beat on the top and bottom lines with revenue in dollars up 36% YoY and 11% above the previous quarter. EPS relative to 2020Q3 is up over 100%, free cash flow is up over 35%,20 while the share price is 20% lower. To be clear, TSMC is not out of the woods yet. Among Q3 earnings was the announcement that capital expenditure would be slashed from the original guidance of at least $40 billion to $36 billion, indicating management still sees some softer demand ahead. This announcement was another hit to the equipment makers, but so much of that pain is already priced in. The likelihood that you look back five years from now at a purchase of TSMC or ASML with regret is very low. Again, there are geopolitical risks, but they extend way beyond chips. And if you are worried that Taiwanese fabs will be captured by foreign forces, then buy Samsung and Intel as they are the manufacturers most likely to benefit (not investment advice!). The chips have to be built somewhere.

Continued progress in the frontier fields of AI, machine learning, simulation, robotics, etc. require the super-sophisticated chips of Nvidia and AMD, and, hence, TSMC. Nvidia isn't exactly cheap, but it is cheap relative to its history over the past three years, and AMD is starting to look cheap given the anticipated growth over the coming decade. It is trading right at the pre-pandemic high with double the 2020Q2 EPS and over 300% the cash flows from operations.21 Aside from technological progress, just a continuation of current technologies expanded to a broader portion of the globe mean way more chips. Less cutting-edge firms like Texas Instruments will see continued growth irrespective of innovation. The world is way too digitized and changing way too rapidly for a persistent downturn in this industry. The question is not whether this becomes a $1 trillion industry, but how quickly it becomes a $1 trillion industry.

The End of the World is Just the Beginning. See chapter "And Now for Something Completely Different"

Federal Reserve History. The Great Inflation

Although many of these periods also involved bottom-up changes (i.e., suffrage movements following WWI, post-WWI Russia revolutions, etc.)

The Economist. The changing American consumer 2022-05-29

McKinsey. Semiconductor shortage: How the automotive industry can succeed 2022-06-10

Wall Street Journal. For Chip Industry, Global Supply Crunch Pushes Next Target to $1 Trillion 2022-01-30

Moore's Law in the literal sense of doubling transistor density every 24 months is over due to the constraints of physics, however, the spirit of the law is alive in doubling computer power every 24 months as innovation continues in areas like 3D transistors

Bloomberg. No Need to Blow Up TSMC in China War, Taiwan Security Chief Says 2022-10-12

The Knowledge Project. Semiconductors: Everything You Wanted to Know 2020-11-23

Semiconductors: Everything You Wanted to Know

Wall Street Journal. Tech Bill Aims to Block U.S. Aid for Companies That Build Advanced Chips in China 2022-07-18

Wall Street Journal. Latest U.S. Chip Curbs Deliver Setback to China’s AI Ambitions 2022-09-01

Foreign Policy. China’s Drive to Make Semiconductor Chips Is Failing 2020-12-14

Wall Street Journal. Intel Posts Sharp Drop in Sales, Issues Muted Outlook 2022-07-28

FactSet. Largest Cuts to EPS Estimates for S&P 500 Companies for Q3 in 2022 in More Than Two Years 2022-09-30 and S&P 500 Earnings Season Update: October 14, 2022 2022-10-14

People love pointing out the sovereign risk for Taiwan when you bring up TSMC. The reality is that a move from China to take the island would have cascading effects across the global economy and market, with massive negative consequences for blue chip firms in the US (i.e., Apple) and across the globe. Gaming out that scenario is a topic for another day. Taiwan should have a higher country risk premium than the US, but that doesn't mean there isn't risk for the US

PP&E spending in 2022Q3 is over 2.5x the 2020Q3 amount, reflecting investment in the business

Free cash flow is actually lower due to a nearly 30x increase in investing outlays

the chips are down, but not out